Welcome 2023: Celebrating Hogmanay at historic sites

Hogmanay fireworks display over the Balmoral Hotel clock tower, with Edinburgh Castle in the distance.

In 2022 the Home Subjects team published its first co-written article, based on our annual tradition of holiday-themed posts dating back to December 2016. It appears as a chapter in Revisiting the Past in Museums and at Historic Sites, edited by Anca Lasc, Andrew McClellan, and Anne Söll, a volume which includes many chapters that will interest the readers of Home Subjects. These include Hannah Scruggs and Tiya Miles on reimagining plantation sites including Berkeley Plantation, Royall House and Slave Quarters, and Montpelier in the wake of Black Lives Matter, Marie-Ève Marchand’s reflections on the meanings of period rooms, Christa Clarke on Yinka Shonibare’s period room intervention at the Newark Museum of Art, and Alexander Bortotlot and Jennifer Olivarez on the Living Rooms initiative at the Minneapolis Museum of Art.

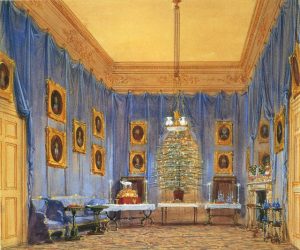

Joseph Nash (1809-78)

The Queen’s Christmas Tree, Windsor Castle, 1845. signed 1845

Watercolour and bodycolour | RCIN 919807

Home Subjects’ chapter, written by Morna O’Neill and Anne Nellis Richter, considers the opportunities and challenges presented by the practice of decorating the historic house interior in the United Kingdom at Christmas. We consider whether such displays can maintain historical accuracy while enhancing the general public’s understanding of the past use of historic interiors through a series of case studies including properties in the care of the Royal Collections Trust, such as Windsor Castle and the Palace of Holyroodhouse, and several managed by the National Trust, including Waddesdon Manor, Chartwell, and Standen. Previous Home Subjects posts have looked at Windsor Castle, Standen and Chartwell. In the chapter, we consider the curatorial goals of these seasonal decorations to argue that historic house museums should not attempt to stave off or deny the presence of commercialism in the holiday but rather introduce the symbols and rituals in a way that both respects history and embraces the enhanced visitor engagement that Christmas decorations can produce. The question of how and why historic properties observe holidays that are religious in nature–seeming to exclude some prospective visitors at a time when the mission of the historic house sector is to expand its appeal–has inspired organizations like the National Trust and English Heritage to embrace a wider range of historical periods and holidays when presenting properties and historic sites. For example, the English Heritage Podcast recently featured Hadrian’s Wall curator Dr Frances McIntosh discussing the history of Roman midwinter festival Saturnalia, and many properties also take advantage of the onset of ‘spooky season’ in autumn, when historically visitor numbers would be starting to tick downward.

BBC presenter Margherita Taylor with Scottish comedian/online tour guide Bruce Fummey and Auchindrain Learning Officer Karen Baird making clootie dumpling to celebrate Hogmanay. Screenshot reproduced courtesy of BBC/Britbox.

Today, to commemorate the publication of our chapter and to ring out 2022, we share a few observations on Hogmanay, a traditional Scottish end-of-year celebration which features the lighting of bonfires, hospitality, and exchanging gifts. Our chapter draws attention to this important Scottish tradition to point out that current practice at the Palace of Holyroodhouse elides festive season practices in Scotland with Christmas as generally celebrated in England, obscuring the importance of Hogmanay in local culture. Significantly, Christmas only became a public holiday in Scotland in 1958. During the Scottish Reformation, religious leaders discouraged the celebration of Yule, a fusion of the Viking Winter Solstice and Christmas, and an Act of Parliament made the holiday illegal in 1640, allowing Christmas to occupy a more significant place in the traditions of the festive season, especially after Christmas began to take on many of the trappings we now associate with it in the nineteenth century. Instead, in Scotland the traditional celebration of New Year’s Eve known as Hogmanay became the central celebration in winter, a tradition which continues to the present day. The city of Edinburgh hosts a three-day festival, culminating in fireworks and street parties. BBC Sunday TV stalwart Countryfile devoted its last episode of 2022 to Hogmanay (available now in the US on Britbox and in the UK on iplayer). The episode was based at Auchindrain Township, the last remaining Highland township to survive widespead clearances in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; it now operates as an open-air museum.

Sir David Wilkie, George IV, oil on canvas, 279.4 x 179.1 cm, signed and dated 1829. Royal Dining room, Palace of Holyroodhouse, image courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust.

The history of royal building and occupation at the site where the Palace of Holyroodhouse now stands dates back as far as the 12th century, long before Christmas was ascendent in either religious practice or popular culture. Holyroodhouse was used as seat of the Scottish court until the early 17th century, when the crown of Scotland was united with that of England and Ireland in the figure of James I in 1603. After suffering extensive fire damage when Oliver Cromwell’s troops occupied it in 1650, the Palace was more or less abandoned for an extended period. Interest in the Palace was revived in the early nineteenth century, when George IV visited Scotland and embraced Romantic-era ‘invented traditions’, including the wearing of tartans as captured in the portrait made to commemorate this visit by Scottish painter David Wilkie. The fortunes of the Palace were truly revived in the early twentieth century, when it was renovated and modernized by King George V. His daughter, Elizabeth II, made yearly visits to the Palace and it became an important site for state ceremonies and diplomatic visits. Possibly because the Palace itself had not been in regular use for several centuries, there is a certain logic to highlighting Christmas decorations in the Palace, as these would have been the focus of the festive season at this site particularly during Elizabeth’s long reign. However, it is disappointing that decorations and celebrations at Holyroodhouse do not address local variations in the observance of the festive season, and the Palace website does not address the particular history of Christmas in Scotland. While Holyroodhouse holds a family day on December 31 to celebrate Hogmanay, most activities on offer are generically festive, such as face painting and “Victorian games,” rather than specific to the holiday. It is to non-state historic sites and organizations like Auchindrain Township, churches, and the ongoing practices of folk tradition like those demonstrated by Scottish comedian and historian Bruce Fummey on Countryfile to which Scots look to mark the New Year.