Spirit Photography and the Domestic Interior

On this Halloween, my mind turned to spirits. Home Subject has considered spooky subjects before, in the context of the British tradition of the festive-season ghost story. In December 2021, Home Subjects posted about M.R. James’ classic tale of a malevolent country house view, and in December 2019 considered Rachel Whiteread’s Ghost in the context of the Victorian haunted house story. Today, I will consider the medium of photography, and the ways in which enterprising Victorians like the American William Mumler used photography to capture the spirits of the deceased visiting loved ones. But how might this connect to the themes of Home Subjects?

Perhaps Mumler’s most famous work is the “Portrait of Mary Todd Lincoln with the Ghost of her husband Abraham Lincoln,” likely taken in 1872. Although even at the time it was dismissed as a fraudulent double-exposure, it nevertheless revealed what many viewers desired from a photograph: the ability to remember a loved one. For some observers, this need tied photography back to the very origin story of art, as related by the ancient author Pliny.

A young woman’s lover was about to go off to war, and she was sure he would not return. She wanted to keep something of him with her. But painting, indeed the very idea of art, had not yet been invented. When she observed him asleep, she traced the outline of his shadow in the soft clay of the wall. Luckily for the maiden, her father was a potter; we can see his kiln burning bright in the background in this inpretation of the scene painted c. 1782-85 by Joseph Wright of Derby. She will cut his silhouette out of the wall, place it in the fire, and it will be a plaque of his image–the first instance of recording the likeness of a departing loved one. Wright of Derby painted this version of the Corinthian maid for his friend Thomas Wedgewood, of the pottery fame.

Less than a hundred years later, the British photographer O. G. Rejlander would adapt the story of the Corinthian maid to the origin of photography. The play of light on the lover’s head cast his shadow on the wall. Similarly, light would burn the impression of a person onto a photographic plate—the meaning of the word photography (a neologism from Greek suggested by the astronomer Sir John Herschel) is “light” “drawing.” It seemed to provide, in the words of Roland Barthes writing in Camera Lucida, the “that has been” of the image.

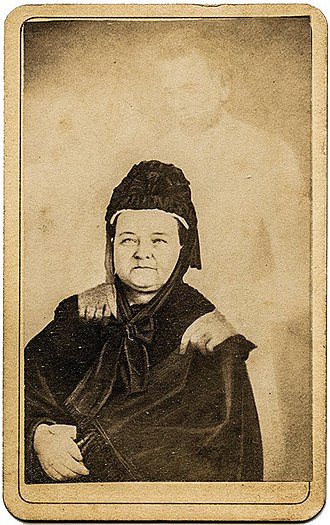

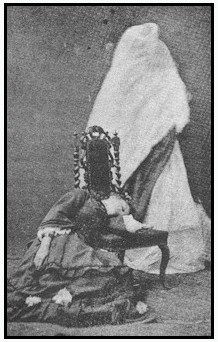

Part of what made Mumler successful was the apparatus of the photographic studio, the “mystery” of what happens when the photography disappeared behind the dark curtain or into the darkroom to develop the negative. The studio was a place for professionals. At the same time, many photographic studios in the nineteenth century evoked the domestic interior in their set-up and backdrops, as evident in the work produced by the photographer Frederick Hudson and the spirit medium Georgiana Houghton. (Today, Houghton may be more famous for her spirit drawings, which she exhibited at a gallery in Bond Street in 1871). When looking at these photographs, such as those reproduced by Houghton in her book Chronicles of The Photographs of Spiritual Beings and Phenomena Invisible to the Material Eye (London: E. W. Allen, 1882), I am struck by the repeated use of what seems to be Jacobean revival furniture in the photographic studio: a stately high-backed chair whose heavy materiality contrasts with the floating drapery of a spirit and a table with elaborately turned legs, supporting the weight of child sitters.

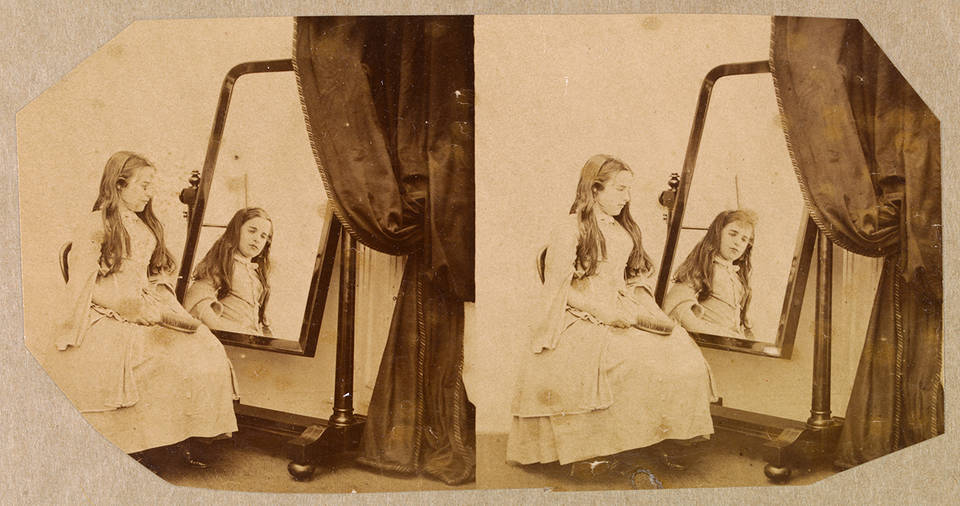

Stereoscopic photograph of Clementina Maude, by Lady Clementina Hawarden, 1859 – 61, England. Museum no. 457:284-1968. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Where these, alongside the rugs and the draperies, merely the standard props available in Hudson’s establishment? Or was their selection more specific? It brings to mind the dramatic poses and sparse interiors evident in Lady Clementina Hawarden‘s work from the early 1860s. She gave over the main public spaces of her home to her photographic practice, using the abundant light from the windows of her South Kensington townhouse to illuminate her practice. Hawarden started out with a stereoscopic camera, each exposure offering an uncanny doubling of the sitters. As if to emphasize this effect, she often used mirrors in her photographs of her daughters, a kind of doubling that seems to pre-figure the eerie apparitions of spirit photographs.

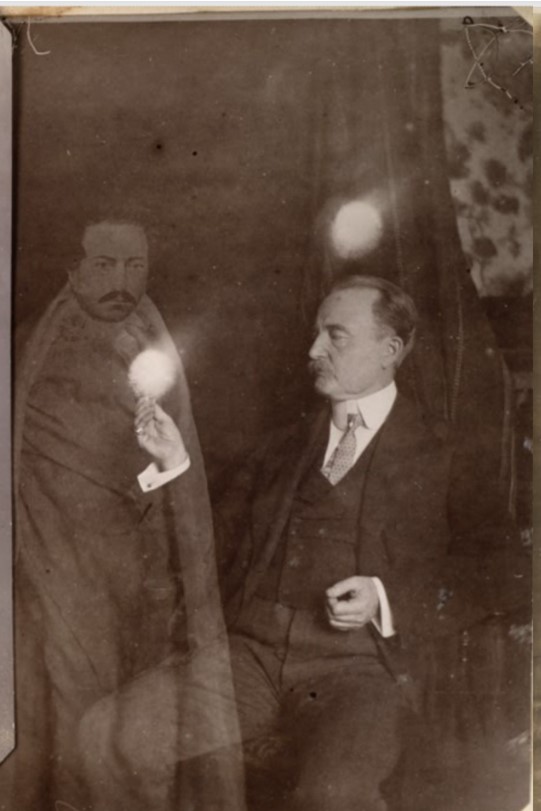

William J. Pierce, Spirit Photographs, ca. 1903 (detail); collection SFMOMA, Accessions Committee Fund purchase.

Other spirit photographers eschewed the professional studio in favor of photographs taken in the home. While the studio provided the aura of professionalism, the domestic setting provided a homeliness to these visitations. Photographs such William Pierce’s Spirit Photographs (c. 1903) seem to capture a ghostly apparition returning home. A striped blanket provides an imperfect backdrop that reveals elaborate floral wallpaper and furniture in the far right. The homes of mediums often provided the background for spirit photographs, as in the case of the medium Florence Cook, who claimed to “materialize” a spirit named Katie King in the Cook family home in Hackney in the early 1870s. Katie King’s “spirit” walked, talked, and held objects. Guests were invited to sit in the parlor as Florence began her séance and entered into a trance, at which time Katie King would emerge. Visitors would be shown Florence lying in her bedroom from a distance while Katie took on physical form in the parlor.

There is a longer history to the phenomenon of a spirit named “Katie King” taking physical form. But what is fascinating from the perspective of the domestic interior are the photographs that were taken to demonstrate that Florence Cook was not merely posing as Katie King. In an effort to establish that that Florence was not merely re-appearing as Katie, she had “their” photographic taken in a studio, where, once again, a Jacobean Revival chair serves as an important prop. In addition, beginning in 1874, Florence consented to a series of séances at the home of the scientist William Crookes. He used five cameras and produced more than fifty photographs that purported to show Florence and Katie in the same frame. The seances took place in Crooke’s home laboratory, while Florence would be in the library, separated by a curtain. These photographs are often cited as definitive proof that Katie was not a materialized spirit (although the exact nature of her act was never disclosed, it is likely that Florence used another woman to take her place on the bed, or had another woman stand-in for Katie). For readers of Home Subjects, they also suggest the fluid nature of domestic space, from the laboratory to the occult.