Checking in on 2023: Upcoming Events

It is always a great time to be interested in “Home Subjects.” But readers who are eager to engage with the display of art in the domestic interior in the Victorian era and beyond have a number of exciting events coming up! This post will provide an overview of some of these events, as well as links for further exploration.

Today is the last day to submit a proposal for the Isokon symposium at the Yale Center for British Art, to be held on Friday, April 21, 2023. This one-day symposium will examine “the Bauhaus of London” that developed in the sleek apartment building on Lawn Road in London, designed by Wells Coates in 1934, with flats outfitted with furniture produced by the British manufacturer Isokon. Home at one time to Marcel Breuer, Walter Gropius, and László Moholy-Nagy, the cultural and modernist influences of Isokon artists and designers informed a progressive model of “art at home.” We’re eager to expand the reach of “Home Subjects” into the twentieth century, so if you are interested in contributing a post on Isokon or other examples, please let us know.

Moving backwards into the nineteenth century, the William Morris Society, in conjunction with the Historic Interiors Affiliate Group of the Society of Architectural Historians, will host an online book event on Friday, February 24 at 1pm EST on “New Books on 19th-Century Interiors” (you can sign up here). Andrea Wolk Rager will discuss The Radical Vision of Edward Burne-Jones (Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, distributed by Yale University Press, 2022), the first scholarly monograph on the artist since 1973. She explores Burne-Jones engagement with artistic media to present him as an artist whose paintings were a form of protest against the injustice of the age. Central to her argument are many of the works that Burne-Jones created for specific interiors, often in collaboration with William Morris. The event will also feature John Holmes, who will discuss his book Temple of Science: the Pre-Raphaelites and Oxford University Museum of Natural History (Bodleian Library and Oxford University Museum of Natural History, 2020). While not focused on the domestic interior, Holmes’s discussion of the Oxford museum nevertheless demonstrates the far-ranging efforts of the Pre-Raphaelites and other artists to bring art into everyday life in the nineteenth century. We hope that future posts for “Home Subjects” will explore each of these publications in greater depth.

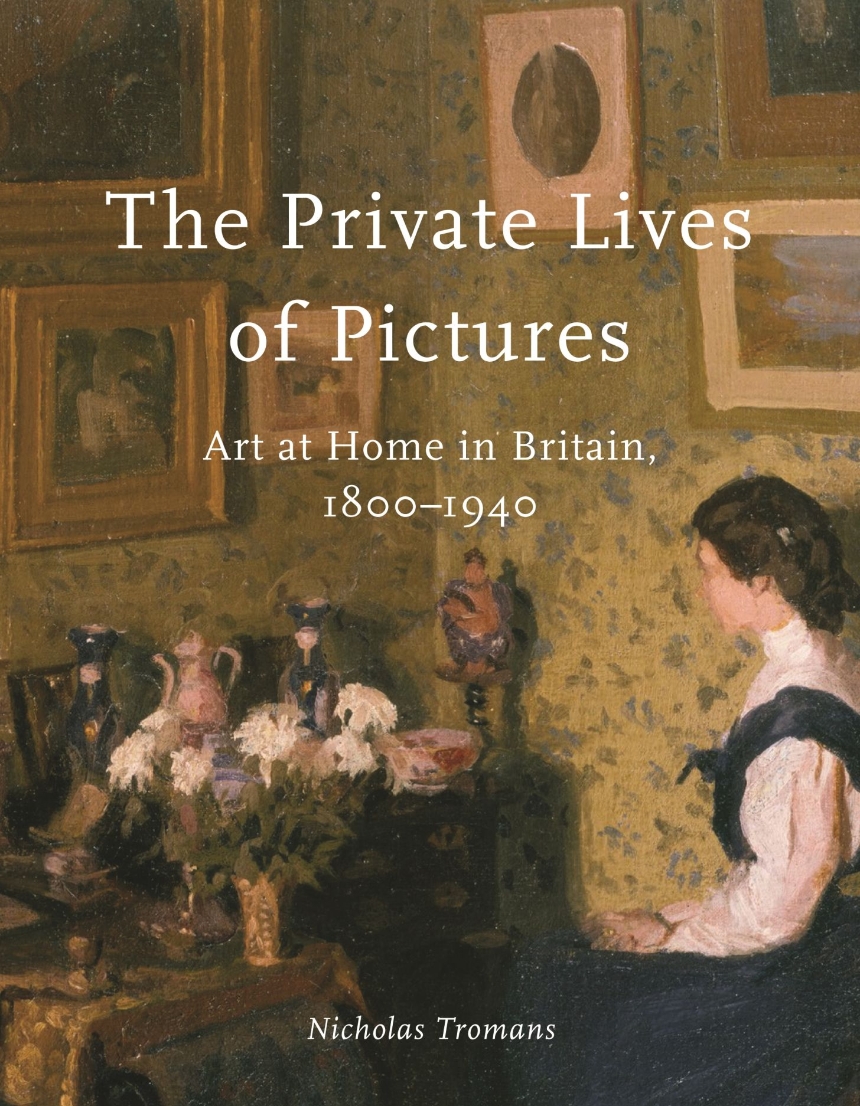

Rager’s book in particular, alongside Nicholas Troman’s The Private Lives of Pictures: Art at Home in Britain, 1800-1940 (London: Reaktion / University of Chicago Press, 2022) demonstrates how attention to the domestic interior can generate exciting new interpretations of works of art. Tromans’s book picks up on themes that he had previously explored in a post for “Home Subjects:” the artistic tradition of melding residence and picture gallery. He places this discussion within a compelling exploration of a deceptively simple question: why display art in your home? The book provides a room-by-room tour of an imaginary Victorian interior, while also exploring the sentimental attachments of home and memory. One of the most exciting aspects of this book are the ways in which the domestic context provides a startling new interpretation of a (seemingly) familiar work. For example, his discussion of Harold Gilman’s “Edwardian Interior” (c. 1907, Tate) considers the ways in which the figure interacts with the domestic space. Gilman painted his sister Irene at their family home, the rectory at Snargate, in Kent, surrounded by pictures and decorative objects. Although the pictures were put up to be looked at, Tromans acknowledges an awkward truth: “who , truthfully, really looked at the pictures in their own home on a regular basis?” Irene is more taken by the Asian-inspired objects on the table, surely more fashionable in 1907 than the small gold-framed paintings on the wall.

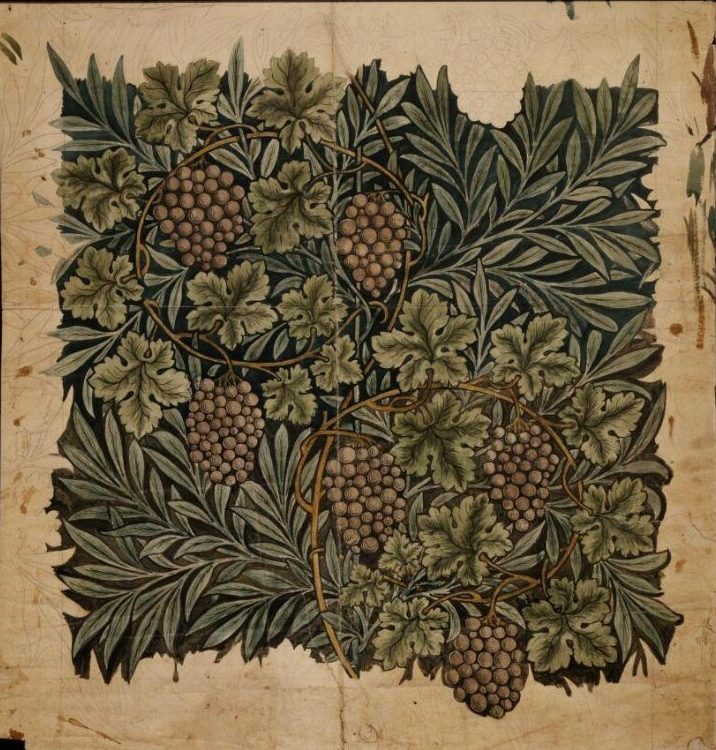

This example calls to mind William Morris’s advice, “Whatever you have in your rooms, think first of the walls!” This quotation is the basis for Stephen Kite’s exploration of the “surfaces of romance” in his new study Shaping the Surface: Materiality and the History of British Architecture, 1840-2000 (London: Bloomsbury, 2022). Kite’s discussion of Morris’s attention to wall surface and decoration in Chapter 2 as one of “layering,” especially at his own Red House, inspired by his love of medieval illuminated manuscripts. This approach brings traditional framed pictures back into an Arts and Crafts philosophy of interior decoration, and it also explains why Morris would design such richly dense wallpaper patterns–these spatially compressed layers recall the pages of a medieval missal, “wall and gate, flowery mead, fruit trees, fountain, and trellis enclosure.” Those interested in new readings of Victorian design philosophy should also be sure to check out the talk by Christine Olson in the Historians of British Art-sponsored session at the upcoming College Art Association conference in New York: “The Surface of the Past: Drawing and the History of Ornament in Victorian Britain.” Further details about the session and the other fascinating talks can be found here.

And, finally, an opportunity for art viewing, with the exhibition “A Marriage of Arts and Crafts: Evelyn and William de Morgan,” at the Delaware Art Museum until February 19, 2023. Organized in conjunction with the De Morgan Foundation, and curated by Margaretta Frederick, the exhibition and its accompanying publication explore the personal and creative partnership between painter (Evelyn) and ceramicist (William). As their friend Emelie Isabel Barrington noted, “I pictured them so entirely as one.” A future post will consider the important catalogue for the exhibition. But the show itself closes soon: catch it while you can!