The Conversation Piece

This month, we are delighted to feature some reflections on the conversation piece by Kate Retford, Professor of History of Art at Birkbeck College. She is the author of The Conversation Piece: Making Modern Art In Eighteenth Century Britain, published for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by Yale University Press in 2017. Kate has spearheaded a number of exciting projects related to British houses and art collections: two of the most recent include a podcast on ‘Marketing the British Country House as Home’, and the essay ‘”A Family Home and not a Museum”: Living with the Country House Art Collection’, in the Paul Mellon Centre’s online publication, Art & the British Country House. In 2015, she co-organized a major conference entitled ‘Animating the Eighteenth-Century Country House,’ a collaboration between Birkbeck, the National Gallery, and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. This was followed by a related event the following year, co-organized by the same institutions: ‘Animating the Georgian London Town House’. This formed the basis of a volume of essays, co-edited by Kate and Susanna Avery-Quash, published by Bloomsbury Academic in 2019 and soon available in paperback: The Georgian London Town House: Building, Collecting and Display.

My book, The Conversation Piece, started with an invitation to speak at a conference on The Georgian Interior at the V&A back in 2005. These small group portraits offer tantalising glimpses of eighteenth-century interiors, filled with carefully represented furniture, ornaments and paintings. It is not surprising that, when they were effectively ‘rediscovered’ in the inter-war period in Britain, critics marveled at the apparent insights they provided into domestic life. Mary Chamot declared them ‘able to transport us into the very atmosphere of English home life at that time’, whilst George Williamson described the conversation piece as ‘a peep-show into the English home’.

I approached that paper with a reasonably straightforward aim of reminding the audience that such paintings should never be treated as proto-photographic snapshots. However, the complexities of the situation ended up keeping me absorbed in a book project for the next ten years!

At one end of the spectrum, some conversation pieces can indeed be neatly matched with historic interiors. Everything visible in Johan Zoffany’s portrait of Sir Lawrence Dundas in his dressing room at 19 Arlington Street, London, can be identified in an inventory taken the previous year [fig 1]. Seven of the recorded ‘8 Antique figures’ in bronze (by Giacomo and Giovanni Zoffoli) and eleven of the ‘29 Pictures’ are visible. Robert Adam’s ‘Pier glass in a gilt frame’, hanging above a ‘large rosewood writing Table’, supporting a ‘figure of Bacchus’, can be seen to the left of the picture. Dundas’s townhouse is now long gone – knocked down in the 1930s to make way for a block of flats – but Zoffany’s picture provides us with an invaluable insight into one of its rooms, giving items recorded in the inventory form and color.

Figure 2. Zoffany, ‘George, Prince of Wales, and Frederick, later Duke of York, at Buckingham House,’ 1765. Royal Collection Trust.

Figure 3. James Stephanoff, ‘The Second Drawing Room, Buckingham House,’ 1818. Royal Collection Trust.

On many occasions, however, such a matching exercise reveals tweaks and adjustments. Other patrons realized that one scrupulously accurate viewpoint into any single interior could never contain as much meaning as an image which expanded those limits. A few years earlier, Zoffany had painted Princes George and Frederick in the Queen’s second drawing room at Buckingham House [fig. 2]. An 1818 watercolour of that space verifies the crimson wall hangings, marble fireplace and red and gilt furniture (shown with covers in the portrait) [fig. 3]. However, the comparison also reveals that, whilst the overmantel mirror (updated by the early nineteenth century) records an actual doorframe, designed by George III himself, the artist has effectively twisted the room in order to include its reflection. He thereby compliments the King, provides additional interest, and enhances the sense of space. Furthermore, whilst the two depicted portraits by Anthony van Dyck were indeed in situ, Zoffany imaginatively moved the painting after Maratti of the infant Christ from elsewhere in Buckingham House to this spot, to provide the ultimate genealogical heritage for the young Princes. The half-lengths of the King and Queen were probably invented, to allow him to complete the nuclear group and create a pictorial family tree.

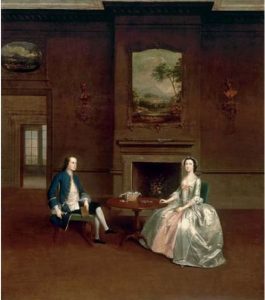

Figure 4. Arthur Devis, ‘Mr. and Mrs. John Bull,’ c. 1747. New York University, Institute of Fine Arts, Conservation Center, currently on loan to the Met.

Figure 5. Arthur Devis, ‘Mr. and Mrs. Dashwood,’ c. 1750. Private Collection.

I got most absorbed, however, in those conversation pieces in which we find completely invented settings – most obvious, and most striking, in cases of replication. Most of the rooms in Francis Hayman’s conversation pieces of the 1740s and 1750s, for example, are made up of an amalgam of imagined elements and studio props which the artist reused time and time again. However, the best and most numerous examples come from the work of Arthur Devis. The room in which Mr. and Mrs. Bull [fig. 4 ]are shown is virtually identical to others painted by the artist: the landscape over the fireplace, the busts, the painting above the doorway, and the view through to the window are reproduced in a portrait he painted of Mr. and Mrs. Dashwood three years later [fig. 5]. Some scholars would, at this point, dismiss the depicted space in the Bull portrait as therefore unable to tell us anything about their house – but such fabricated, recycled interiors are invaluable. Although the Bulls were much less wealthy than Dundas, my overall conclusion was that these were not aspirational interiors, not least as typically filled with perfectly credible items – indeed, even a little on the sparse side. They were instead intended to indicate appropriate, decorous homes, showing widely approved and popular items and décor – presenting a ‘mean of good taste’. They thus give us an invaluable insight into contemporary standards, into the ideas and ideals in the minds of such consumers when they were thinking about which goods to buy, and when they were looking at (and judging) the homes of their neighbors.

I also concluded that the Dundas and Bull portraits have something key in common. Both are essentially poems to the eighteenth-century material world: to the products of the age; to the most valued materials of the day; and to the manipulation of those materials through the skill of craftmanship. The mahogany table in the Bull portrait is generically ‘good’, whilst that in the Dundas painting is real, particular and bespoke. However, both are studies of well crafted furniture, made from an increasingly imported and popular fine grain wood, valued for its deep red-brown colour and its ability to take a high shine.