Holly and Ivy: Decorating for a Tudor Christmas

In December 2016, Home Subjects inaugurated a tradition of yearly posts exploring the history and implications of decorating for the festive season in historic houses and museums. (The first is linked here, while others are linked in the text below.) We are delighted to announce that an article expanding upon the ideas generated in these posts will soon appear in a volume titled Space Unlocked, History Unfrozen (Bloomsbury 2021) edited by Anca Lasc, Andrew McClellan, and Änne Söll. Today we share some further discoveries made during the course of researching and writing the forthcoming article.

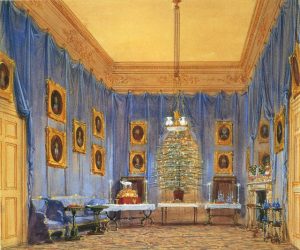

Joseph Nash (1809-78)

The Queen’s Christmas Tree, Windsor Castle, 1845. signed 1845

Watercolour and bodycolour | RCIN 919807

As we have written here in the past, it is widely-accepted lore that the Christmas tree and many of the other decorative trappings of Christmas were introduced to Britain by Prince Albert during the Victorian period. As the story goes, Albert wanted to share these traditions, which were familiar from his youth in Germany, with his young family. There is some truth in this story, yet as we discovered, historians of Christmas debate whether Christmas was invented, discovered, reinvented, or constructed in the Victorian period. Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger have described how even traditions that appear “ancient” and linked to “an immemorial past” can be relatively recent, especially in relation to the British monarchy. The 1830s and 1840s were a period of the rapid expansion of the Christmas industrial-complex in Britain, encouraged not only by the richly-adorned trees surrounded by gifts installed at Kensington Palace, but also of the proliferation of illustrated holiday keepsake albums and the first commercially-printed Christmas cards. Such pre-printed Christmas cards are an invention the V&A Museum attributes to its founder, Sir Henry Cole, who sent out the first such card in 1843—also the year that Charles Dickens’ story A Christmas Carol was first published, its initial print run of 6,000 copies selling out in a mere five days. These traditions may not have been so much invented during the Victorian period, but supercharged by commercialism.

In recent years, the historic house sector, led by institutions like Historic Royal Palaces, The National Trust for England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and the Museum of the Home, has embraced seasonal exhibitions, and indeed, visitor numbers and income are so strong over the festive period that they have come to represent a significant (and essential) percentage of the yearly budget. In many cases, displays and exhibitions in these houses focus on Christmas celebrations from the Victorian period or later, but this approach does not work for properties whose architecture or main period of historical interest precedes the nineteenth century. For today’s post, we highlight some of the older traditions that can be drawn upon by historic properties and museums during the festive period.

From the Middle Ages onward, Christmas celebrations were focused on aristocratic largesse and charity. By the eighteenth century, aristocratic traditions included feasts for tenants, often with entertainment, as well as decorating houses and churches with holly and ivy. (Holly and ivy were particularly appropriate for the season, being traditional Christian symbols for Christ and Mary, and are celebrated in the traditional English carol ‘The Holly and the Ivy’—though this carol cannot be definitively dated before the early nineteenth century.) Yet, these traditions were not exclusive to the upper classes; even working people would have marked the holiday (beginning at midnight on Dec. 25 and continuing through the twelve days of Christmas) by refraining from some types of work and decorating their homes. In a recent BBC documentary (also available now on PBS) Lucy Worsley, curator at Historic Royal Palaces, and Jon Roberts, a historian of rural life at the Weald & Downland Living Museum, demonstrate how greens were used to decorate houses in the countryside. Worsley quotes an account dating back to the twelfth century which asserts that “Every man’s house, as also their parish churches, was decked with holly, ivy, bay and whatsoever the season of the year afforded to be green.”

Geffrye Museum (now renamed Museum of the Home), London, Christmas Past exhibition, 1630 Hall with Christmas decorations and feast. Photo courtesy of Museum of the Home.

The focus on seasonal greens and representations of period feasting have been important touchstones for museums and houses focused on periods before the nineteenth century. In 2016, we wrote about the Museum of the Home’s annual “Christmas Past: 400 Years of Seasonal Traditions in English Homes” exhibition. This museum, which traces the history of the domestic interior through a series of interiors dating from 1600 to the present, is ideally placed to show audiences the evolution of Christmas decorating traditions over time. Curator Hannah Fleming explained, “In the seventeenth century, it was New Year’s Day that was the high point of the festival season. Christmas itself was associated with rowdy behaviour. It was seen as a church-endorsed license to misbehave in a way you couldn’t get away with the rest of the year.” So, for example, a room representing a middling-class home in the 1630s is decorated only with greenery on the hearth and candles on the table–the focus of the display is the array of sumptuous–and luxurious–sugary sweets. Click here to see a short tour of the exhibition, in which Fleming explains some of these seventeenth century traditions in detail. (The museum, which was recently renamed, has been closed for nearly three years for a major redevelopment, but is currently set to reopen in early 2021.)

Likewise at The National Trust, managers and curators of properties dating to sixteenth and seventeenth centuries often mark the festive season with period-appropriate decorations. For example, at Cotehele Manor in Cornwall, a yearly tradition is to recreate a family garland in the Great Hall. The garland is made from flowers grown and dried on site, further deepening visitor understanding of the relationship between such tradition and the house and its landscape, not to mention the relationship amongst aspects of the property’s management during different seasons of the year. Many properties also layer in sensory elements, such as displays of period-appropriate foods (fruits and ‘marchpane’—a sugar paste decoration) and period music to attract audiences. Examples include Greys Court in Oxfordshire and Little Moreton Hall in Cheshire.