CAA 2021 Session: A New Story about British Culture? The Rhetoric of Display

The College Art Association annual conference begins this week in its virtual format, and the Historians of British Art have sponsored a session chaired by Julie Codell that will appear to Home Subjects readers. We’ll be perusing CAA Abstracts for other relevant papers or sessions, and we’ll also try to post more about upcoming virtual events with a Home Subjects-related appeal. In the meantime, if you have an event of interest, please let us know at [email protected].

A New Story About British Culture?: The Rhetoric of Display

Live Q&A: Thursday, February 11, 2021; 4 pm – 4:30 pm EST. [You can participate in the Live Q&A by registering for the conference. All access for CAA members is $249 or you can purchase a $99 day pass].

The Metropolitan Museum’s $22 million reorganization of its British galleries and 2020 re-opening of its 11,000 square feet devoted to British decorative arts, design, and sculpture created between 1500 and 1900 evokes a rethinking of British visual culture and its modes of display. Panels may investigate the themes of this reorganization in the Met’s exhibition or in other transforming exhibitions in any institutions in the UK or its colonies from the past until now: (1) the colonial roots of British material culture, (2) the commercialism driving British design, and (3) socio-political hierarchic relations among cultural objects and their producers. In this panel we will examine these topics within the overarching consideration of the rhetoric of display: how display narrates / represents intertwined economic and aesthetic values or the connections among culture, empire, and slavery.

Chair: Julie Codell, Arizona State University

Presentations:

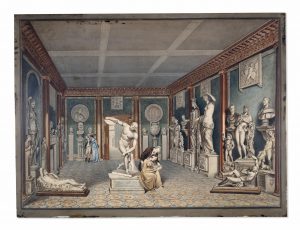

- Re-contextualizing the Townley Gallery of the British Museum 1808-1823: Museums, Collecting, Empire

Nicole Cochrane, University of Exeter

- The Samuel and Mary Bancroft Collection of Pre-Raphaelite Art: Re-installed and Re-contextualized

Margaretta S. Frederick, Delaware Art Museum

Saralyn Rosenfield, director of learning and engagement; Heather Campbell Coyle, chief curator and curator of American art; Margaretta Frederick, curator of the Bancroft Collection; Amelia Wiggins, manager of gallery learning and interpretation prototyping the Pre-Raphaelite gallery at the Delaware Museum of Art. Photo by Stacey Mann, courtesy of the Delaware Museum of Art.

- Re-interpreting the Aesthetic House Beautiful: The Russell-Cotes Art Gallery and Museum

Anne Claire Anderson, Exeter University

In 1897 Merton Russell-Cotes, hotelier extraordinaire, planned the house of his dreams, East Cliff Hall. Completed in 1901 as a birthday gift for his wife Annie, the house was crammed with the couple’s collections which had formerly graced the Royal Bath Hotel. Here they created a sophisticated ambience for the hotel’s elite clientele which included Oscar Wilde and Prince Oscar of Sweden. Relocated to East Cliff Hall these objets d’art continued to be prized for their decorative effect, contributing to an ensemble known at the time as a House Beautiful. In 1908 Merton and Annie gifted the house and much of the contents to the city of Bournemouth. With three purpose built galleries added, the Russell-Cotes Art Gallery and Museum was officially opened in 1919. As a public institution the mission of the Russell-Cotes became clouded: was it intended to embody Victorian taste in interior décor as an art gallery or a museum? Furniture and ceramics told different stories as mementoes and souvenirs adding to Merton’s and Annie’s history and as culturally valuable artworks placed in an art historical framework/hierarchy and subject to cross-cultural, colonial interpretations. There are plenty of “unsung heroes” at the Russell-Cotes, as Merton collected commercial manufactures: one looks in vain for Morris and Dresser. Rather one finds Royal Worcester and Crown Derby, alongside Parian and Bisque figures. In my paper I track the presentation of selected objects from hotel curios to culturally valued works of art to illustrate the rhetoric of display.

- The Met’s New British Galleries, 2021

Wolf Burchard, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

An installation view of a 19th-century room in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new British galleries Photo by Joseph Coscia, February 2020/Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In this presentation I will highlight the Met’s new British Galleries and provide a summary of both the curatorial and the design decisions that were the foundation for this large renovation project. The new galleries seek to present the history of British decorative arts in a more nuanced light, focusing particularly on the creativity and entrepreneurship of British manufacturers. The goal of the curatorial team, which initiated this project, was to move away from a traditional presentation of their collection in the context of aristocratic patronage and the British country house (very much in the vain of the “Treasure Houses of Britain” exhibition, mounted at the National Gallery of Art in Washington in 1985) and to tell the story of the international cast of characters that markedly shaped British design over 400 years. The new physical and intellectual interpretation of the Met’s collection of British furniture, sculpture and decorative arts is designed to allow for a dynamic and ever changing display that will keep both the museum and its visitors engaged in ongoing cultural discussions.