The Healthy Home (Victorian Style)

When I began planning a blog post for March, I was casting around for a timely topic. Maybe something about the display of art in the Irish interior in honor of St. Patrick’s Day? Or an examination of the Mario Buatta sale at Sotheby’s in January? The “Prince of Chintz” was famous for his madcap adaptation of English country house style (the dogs! the bows!) and had been considered “out of style” at the time of his death. Yet the sale resonated with millennials, prompting designer Thomas Jayne to wonder, “Is there now going to be a cascade of people putting bow knows over their paintings? Bow knots in Bushwick?” We can only hope.

The sale also continued the trend of auction houses “re-creating” or “staging” famous interiors at their offices. Rush Jenkins, in charge of the Buatta recreation for Sotheby’s, noted, “We wanted to make it as authentic as possible, so people could feel they had stepped into the life of Mario Buatta.” Can you tell the real Buatta living room from the ersatz Sotheby’s version? (Hint: one has film-set lighting and lacks an exit.) Perhaps Millennials were responding to the tyranny of mid-century modern, the austere parameters of their own style and “the Tyranny of Terrazzo,” as Molly Fischer recently termed it. If you are craving more, more, more Buatta, the estate will generate further sales at Stair auction galleries in Hudson, New York.

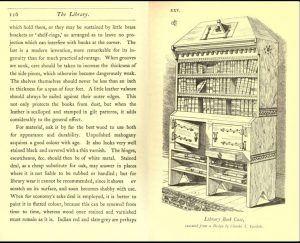

Before I could write that post, however, a global pandemic intervened, and along with it, the closure of schools and the need to transition to online learning. And like many people, my mind is on topics other than “Home Subjects” even as I’m spending a lot of time at home. I’m noticing that some things aren’t so clean; cluttered surfaces, dusty shelves, and long-postponed filing projects abound. I was reminded of Charles Eastlake’s advice in Hints on Household Taste, first published in 1868, to put doors on bookshelves to protect leather bindings from airborne threats. Eastlake’s uncle Charles Lock Eastlake had his own concerns with dust as the Keeper of the National Gallery; he had been excited to learn that Gustav Waagen cleaned the paintings in the royal collection in Berlin with a feather-brush. In fact, dust is a villain in Eastlake the younger’s book, and any decoration that encourages the gathering of dust, from long curtains to large carpets, should be avoided in search of a “healthier” home.

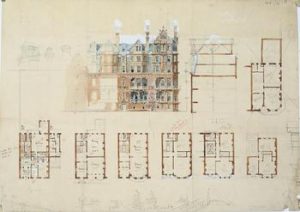

Designs for 4-6 Chelsea Embankment and the corner of Tite Street, London, for Messrs Gillow and Company. RIBA.

Isn’t that what many are seeking right now? A home that promotes both physical and psychological health as we hope to prevent the spread of infection for the benefit of ourselves, our loved ones, and the world we inhabit? Many artists and commentators associated with the Aesthetic movement and the Arts and Crafts movement promoted interior design as one component of a healthy lifestyle. They advocated for indoor plumbing, fresh air, and ventilation. A wonderful article by Richard W. Hayes in Architectural History discusses the Aesthetic Interior as an “Incubator of Health and Well-Being.” Hayes connects the work of the architect E.W. Godwin to the goals of the “sanitary movement,” spearheaded by the physician Benjamin Ward Richardson. Richardson was a pioneer in the field of public health who vigorously pursued advances in areas ranging from the development of anesthesia to the humane treatment of animals raised for food. Richardson’s ideas about household cleanliness were extremely influential, and Godwin incorporated many of these into his designs for Bedford Park, a planned community in Chiswick in West London. Godwin designed architectural features such as ventilation spaces beneath houses and specified washable material–like glazed brick–for walls. Godwin’s engagement with the goals of the sanitary movement continued in 1877, when he designed three homes on the Chelsea Embankment (recently created by the construction of a sewer system for London) with a commission from the furnishers Gillow and Company. Now that sewage no longer drained into the river, maybe people would want to live nearby?

Hayes’s article provided me with a new perspective on an icon of the Aesthetic movement: Godwin’s ebonized sideboard, now in the collection of the V&A. Hayes writes, “In contrast to most sideboards of the era…the sideboard has no solid back that would create corners to entrap dust or crumbs. It is also less than six feet tall, so that the tops of the closed cabinets can be reached for dusting. The very lightness of the constituent wood framing also reveals the designer’s concern with simplifying housekeeping, for the whole sideboard could be easily moved when the room needed to be dusted or swept. Even if left in place, it allowed for ease of room sweeping, for the lower shelves stand on thin legs about nine inches above the floor.”

The sideboard is a brilliant example of Aesthetic movement functionality, an idea rarely associated with the Aesthetic movement in the popular imagination. We may not be able to have Godwin furniture in our home, but we can feel a bit better by getting out the vacuum in these anxious times.