On a chilly Sunday afternoon in March 1806, George Leveson-Gower, the future 2nd Duke of Sutherland, took a moment from his studies at Christ Church College, Oxford, to write to his mother. The letter was full of news about school and requests for money, but as an aside he took a moment to report on a visit a friend of his, W. Jackson, had recently made to Cleveland House, the luxurious London townhouse owned by his parents, the Marquess and Marchioness of Stafford. Renovations on the house had just been completed, and its interior now included of a large, multi-room gallery suite in which to display the family’s renowned collection of continental masters. Declaring his friend “very much pleased” with the house, he then evokes the kind of vision of the aristocratic townhouse that we so rarely find in this period–the view from the *exterior*. Giving voice to Jackson’s report, George writes, “He wonders what People in the Park if any there were at the time, wd take him & my father to have been, as he says they were flitting ….for about an hour with one candle to see Pictures with wch however he was delighted.”

Without using the word explicitly, Jackson images that seen from outside in the late winter gloom of the park, the darkened gallery might appear haunted by a spirit “flitting” from picture to picture with but one candle to illuminate its way. I found this wonderful quote many years ago in letters archived at the Scottish National Library. It is so evocative of the many themes that we might think about when considering a gallery of art. Though the gallery was purportedly open to the “public,” in practice access remained elusive but to the few who could claim acquaintance with the Marquess of Stafford; his son’s friend might receive a candlelight tour, but those souls in the park could but imagine the splendour the interior contained. Organized according to national schools, the gallery at Cleveland House followed the most up-to-date practices in order to present the art it contained within intellectual and rational frameworks of knowledge; to playfully suggest a ghost wandering its newly-built halls mostly ran counter to the spirit of enlightened connoisseurship its owners were at pains to produce. But in the spirit of Halloween, I wondered whether galleries in private houses might be the type of rooms that were particularly likely to be haunted.

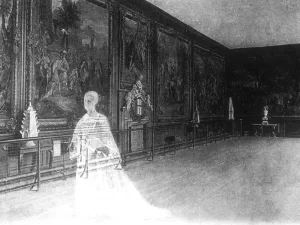

Artist’s conception of Catherine Howard haunting the Long Gallery at Hampton Court Palace. Apic/Getty Images

The gallery as a room type dates back to the sixteeenth century at least, and as spaces where family portraits were often to be found, would seem to lend itself particularly well to haunting, the persistent memory of past lives manifesting in the present. Even so, my search did not turn up as many recorded examples of “haunted” galleries as I hoped. The best example is the Haunted Gallery at Hampton Court Palace. It 1541, Catherine Howard, the fifth wife of Henry VIII ran screaming down the long gallery when she learned she was to be charged with adultery. She sought Henry’s forgiveness, but was executed three months later. Her ghost, it is said, re-enacts these events and has been seen and heard running through the gallery many times over the centuries.

E.F. Benson’s 1911 ghost story, “How Fear Departed the Long Gallery,” which tells the tale of the Peveril family. As with many such stories, Benson’s was written as a Christmas offering; we at Home Subjects have previously explored the phenomenon of the English Christmas ghost story, here and here. The Peverils take great pride in their stately home, Church-Peveril House, and the many ghosts of long-dead relations who shelter under “its acre and a half of green copper roofs.” Amongst them are such spirits as the “Blue Lady” who likes to frighten the family dog in the garden, or “Master Anthony” the ghost of a “foul ruffian” who had likewise been known in life as a “tremendous fellow.” The family takes a very lighthearted view of all of these hauntings but one, the ghosts of twins killed in the gallery by their uncle Dick in 1602, who was to inherit if his brother’s children did not outlive him. The murderous uncle Dick did inherit, but less than a year later met his own untimely end.

Marcus Gheeraerts the younger, Portrait of Two Brothers, oil on panel, 1586. Birmingham Museums Trust.

Soon afterward, the ghosts of the twins were seen moving down the gallery for the first time. After this moment, family legend held that every time the twins were seen in the gallery–thankfully, a rare occurrence–the person who saw them soon perished. In approximately 1760, Mrs Canning, a beautiful and intelligent woman who counted M. Voltaire amongst her friends, decided to prove the superstition wrong by purposely staying in the Long Gallery night after night until the twins appeared. Mrs Canning writes triumphantly to Voltaire of her accomplishment, but soon her beautiful face is overtaken by mysterious natural growths in the form of lichens and mushrooms, and she soon perishes.

Although it is known to be a place of danger after sundown, the Long Gallery is described as a space of active enjoyment and family sociability. “During the day the long gallery is frequented by many occupants, and much laughter in no wise sinister or saturnine resounds there. When summer lies hot over the land, those occupants lounge in the deep window seats, and when winter spreads his icy fingers and blows shrilly between his frozen palms, congregate round the fireplace at the far end, and perch, in companies of cheerful chatterers, upon sofa and chair, and chair-back and floor. Often have I sat there on long August evenings up till dressing-time, but never have I been there when anyone has seemed disposed to linger over-late without hearing the warning: “It is close on sunset: shall we go?”

At this point, our narrator brings us to present, telling the story of a woman who mistakenly falls asleep in the Long Gallery on New Year’s Eve, and upon awakening after dark, seems destined for a terrible fate. Yet she manages to lift the twins’ curse through an act of empathy which I will leave readers to discover. Long Galleries, as noted above, were important spaces for the palimpsest of family history to be recorded. As described in E.F. Benson’s story, they were spaces of family togetherness but also functioned as places of memory where the very worst crimes of family members were memorialized, and in the case of

Uncle Dick, allowed to play out again and again as centuries passed. That his own portrait continued to hang over the fireplace, a portrait described as an image made “in the insolent beauty of early manhood, attributed to Holbein.” That such a portrait could be allowed to remain on view in light of the unspeakable acts that he had committed in this very room suggests the hold of family history over the denizens of such ancient houses, who seem incapable of breaking free of the horror of past violence. Moreover, as these tales of haunting imply, such cycles would be ritually renacted until proper redress for victims of family trauma could be offered. Perhaps the instincts of Oxford student W Jackson, who somehow intuited that there was an undercurrent of menace in even the newly-built gallery at Cleveland House. The collection did not have a family history, but built primarily of works sold in the turmoil of violence surrounding the French Revolution, had its own troubling past that its new owners could never completely dispel.