CFP ASECS 2023: Visualizing the Natural World in the Long Eighteenth Century

Paul Sandby, Fresco from The Painted Dining Room at Drakelow Hall. Great Britain, 1793. Victoria & Albert Museum.

The Home Subjects team will be hosting a session at the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies meeting to be held March 2023 in St Louis, Missouri titled “‘Nature Display’d’: Visualizing the natural world in the long eighteenth century.” Please find the full Call-for-Papers at this link; proposals are due Oct. 3 and we invite you to join us for what promises to be a stimulating conference and session.

This panel seeks to explore the developing awareness of the impact that human activity had on the natural world during the long eighteenth century (1688-1815) and its expression through a wide range of visual media and material culture. Over the course of the eighteenth century, the taste for natural forms was expressed by a variety of theoreticians including figures like J.-J. Rousseau and William Hogarth; Theories about nature, and particularly their influence on the development of landscape painting and on trends in interior design, have long been the focus of art historians. However, the emergence of global networks of exchange alongside forms of industry and technology that left increasingly noticeable and unavoidable traces of human presence on the natural world in ways that permeated the literary and visual arts. Certainly, painters, printmakers, and sculptors explored these themes in their work, and we welcome papers seeking to shed new light on how artists navigated the depiction of nature in the context of an increasingly globalized and industrialized world and in relation to issues like race, gender, and class. In addition, we hope this panel will be able to expand the discussion to explore how the makers of everyday and luxury objects, interior designers, architects, and garden designers thought about and visualized relationships between humans and their environment across the full range of media that constituted the visual field of the global eighteenth century.

François Cuvilliés the Elder, Johann Baptist Zimmermann, and Johann Joachim Dietrich, Hall of Mirrors, Amalienburg Palace, approx. 1734-1739. Schlossanlage Nympenburg, Munich, Germany.

At first glance, the connections between the preoccupations of Home Subjects and the session themes outlined above may seem tenuous, but the house and the interior, both important centers of human activity, were deeply intertwined with attitudes toward nature and land use whether in rural or urban environments. Houses in rural settings, particularly the grand houses that tended to be represented in writing and imagery in the period, often sat in landscapes or gardens that were designed to augment and enhance the lives of the people within. Whether these were working farms, kitchen gardens, parterres full of bedding plants, or vast parks made by garden designers, the landscape was an important symbolic frame for the house, and those who lived and worked in the domestic interior were keenly aware of the interdependence between the two. Stylistically, the fashion for interior design inspired by nature persisted throughout the century. These include such famed interiors as the Hall of Mirrors at the Amalienburg Palace, which combines large mirrors reflecting the garden outside with outrageously intricate rococo stuccowork featuring trees, fruits, flowers, and animals to examples of immersive spaces like the picturesque painted dining room Paul Sandby made for Drakelow Hall in the 1790s.

However, the domiciles of urban-dwellers also exhibited traces of the interpenetration of the interior with the outside world and the vagaries of weather and pollution. For example, as Hyejin Lee has written on this blog, pollution was a longstanding urban problem; the luxurious vessels known as potpourri responded to concerns about the health effects of putrid air in Paris. The development of large parks and garden squares in European cities was likewise in part intended to alleviate the dirt and crowding of cities by introducing sites where trees, flowers, and fresh air were available–at least to those who could access them. Paul Sandby himself enjoyed a studio built in his garden at his residence in Bayswater, depicted as a hive of activity. And of course, as scholars like Elizabeth McKellar and Vittoria di Palma have argued, the landscapes found in between in the largely unplanned suburban fringes, where houses and landscapes intermingled in unexpected ways, or in the ‘wastelands’ found across the country, where landscapes were untamed, unlovely, and even menacing.

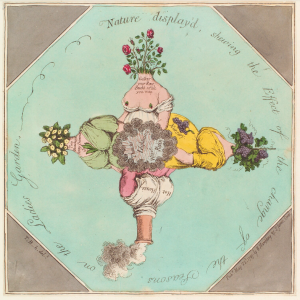

James Gillray, ‘Nature display’d, shewing the effect of the change of the seasons on the ladies garden’, published by Hannah Humphrey

hand-coloured etching, published 22 May 1797. National Portrait Gallery, London, UK

The title of the session was inspired by a 1797 caricature by James Gillray, which uses the theme of a garden throughout four seasons to suggest the extent to which humans (and particularly, “the Ladies”) were implicated in shaping nature to their own ends. The seasons progress by way of the surrealistic imagery of sprays of flowers and fruits springing from the busts of a series of female bodies; at bottom, plant material is replaced by a chimney represting a Hot House, a category of structure that became an important garden structure at larger country houses and in urban areas. Hot Houses, which related to a wide range of other garden and agricultural buildings that blurred the boundary between the practical and the ornamental, permitted their owners to access an ever-expanding list of fruits and vegetables from warmer climates. This upside-down figure hints at the notion that humans had ever-increasing influence over the seasons themselves; at the same time, the image’s title, ‘shewing the effect of the change of the seasons on the ladies garden,’ when considered in relation to the image, suggests that nature had the power to superimpose itself on the human body, in a symbiotic relationship over which neither party could claim supremacy.

Many objects designed for the interior were likewise intended to allow humans to control experiential aspects of daily life such as illumination, or serving food. Many dinner services depicted landscapes and natural forms; the plate seen at left was unusual for its naturalistic depiction of shells artfully strewn on an atmospheric beach. How did diners think about the relationship between the food on their plates and the natural and man-made landscapes from which they had been harvested? We hope that this session will inspire scholars working on a wide range of topics to explore the relationships between eighteenth-century people and the natural world from a variety of perspectives, from the intimate–as suggested by this plate–to the expansive.