Canova at Home: In Memory of Christopher Johns

Ardent football fan Christopher Johns proudly wearing his Vanderbilt Commodores cap (John Russell/Vanderbilt University)

We at Home Subjects learned with great sadness of the passing of Christopher M. S. Johns, the Norman L. and Roselea J. Goldberg Professor of Fine Arts and professor of history of art and architecture at Vanderbilt University. I had the pleasure of working with Christopher when I was a Mellon Teaching Fellow at Vanderbilt. He was an engaging teacher, a capable administrator, and an exemplary scholar. And he was also an inveterate decorator of his interior spaces. His careful attention to detail informed his inviting adaptation of the neo-classical idiom to his home in suburban Nashville, and it was a pleasure to listened to this skilled raconteur hold forth at a table framed by Doric columns and laden with Waterford crystal. As he once told me, “this boy can decorate!” I was reminded that Christopher’s interest in the domestic interior likewise informed his ground-breaking scholarship on Antonio Canova, not least in his essay on the Empress Josephine’s collection of sculpture by Canova at Malmaison. As a way to honor his memory, I’ll revisit some of the keen insights in his essay and review how the scholarly consideration of sculpture in the home has evolved over the past decade. -MO

Antonio Canova (1757-1822), Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker, 1806, marble, Apsley House, Hyde Park Corner, London

Christopher presented Canova as an artistic diplomat par excellence in his important book Antonio Canova and the Politics of Patronage in Revolutionary and Napoleonic Europe (California, 1998). His study established that Canova’s career flourished in turbulent times thanks to the artist’s ability to cultivate ambivalence, both aesthetic and political, in his persona and his sculptural imagery. Take, for example, Canova’s Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker (1806), commissioned by Napoleon and likely intended for an interior setting. The Emperor, however, famously rejected the work as “too athletic” and it entered into the collection of the Louvre. After the Bourbon restoration, Canova offered to re-purchase the work, but the French government instead sold it to the British. The Prince Regent presented the work to the Duke of Wellington, and it was moved to the stairwell at Apsley House, the Duke’s residence in London, in 1817. Even in this brief summation, questions abound, chief among them: how did Canova’s complicated feelings about Napoleon and his actions in Italy play into this commission and its (eventual) domestic display in London? Christopher’s book delves into the complicated interplay of patronage, politics, and sculptural aesthetics around this work. He considers it a “singular failure” for the artist and argues that its placement at Apsley House functions as a kind of prison, with the balustrade forcing the monumental work into a niche that “claustrophobically imprisons” it.

(Image: Photo by Arcways, Inc., Courtesy of Houzz), from https://canvas.saatchiart.com/lifestyle/inspiration/5-of-our-favorite-ways-to-showcase-sculpture-at-home

I think Christopher would have found this comparison amusing: recent advice from Saatchi Art on “five of our favorite ways to display sculpture in the home” included the dictate to “if you have the space to play, let your sculpture steal the show!” As they advice readers, “Life-sized — or larger than life — statement works are stunning all on their own, provided your home has the space to pull off this kind of display. Go bold and feature large freestanding sculpture to really make a statement.” The accompany photograph featured an unnamed contemporary sculpture of blasted wood in the same position and relationship to the balustrade as Canova’s “Napoleon” at Apsley House. It seems that Wellington decided to “go bold” with his decorating choices.

François Gérard, Portrait of Josephine de Beauharnais, 1801, oil on canvas, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

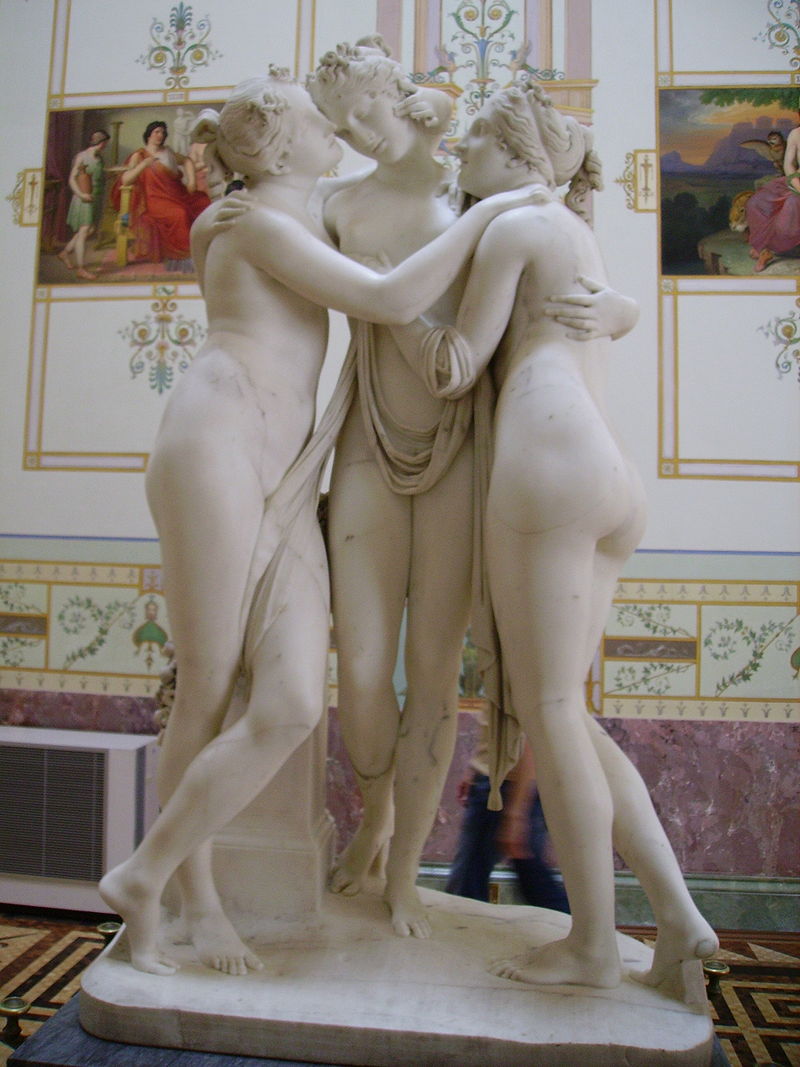

Johns most directly addressed the conjunction of taste, sculpture, and the interior in his article in the Journal of the History of Collections on Empress Josephine’s collection of sculpture by Canova displayed at Malmaison, the home that Josephine shared with Napoleon. She set about creating a domestic retreat and showpiece, with tasteful interiors and an ambitious garden full of rare and exotic flora. Josephine received the house as part of her divorce settlement, and she continued to refine its decoration and plant cultivation until her death in 1814. As part of the decorative scheme, she transformed the grand gallerie into one of the finest private collections of works by Canova in the world, including Cupid and Psyche Standing (1801-4, marble, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg) and The Three Graces (1813-6, marble, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg). Thanks to Christopher’s careful research, it is impossible to think The Three Graces without considering its connection to Josephine and its display at Malmaison.

Unusually, Josephine suggested the subject to the artist, and the arrangement of the three female graces in the context of the domestic environment suggests that Josephine herself completes the group, standing in for the goddess Venus. It is unfortunate that no images of the installation of these works at Malmaison are available for interpretation, yet Christopher nevertheless makes a compelling case for Josephine as a sensitive and generous patron, one of the few who commissioned original works of art from the artist. It is easy to imagine the pride of place given to The Three Graces at Malmaison. Josephine’s son sold other works by Canova to Czar Alexander I in 1816, and the The Three Graces entered the Russian collection in 1866. The home itself changed functions numerous times before being donated to the state in 1904 by the philanthropist Daniel Osiris. It opened as a museum in 1906, but the Canovas never returned. Although Johns does not privilege the idea of the domestic display of these works, his discussion nevertheless suggests many of the issues that animate current scholarship on neo-classical sculpture, providing a useful French comparison for the many excellent studies of the display of classical and neo-classical sculpture in the townhouses of London and country houses throughout the United Kingdom. (And it is worth pointing out that the Museo Canova in Possagno, Italy provides yet another example of domestic display for these works.)

Many of these threads emerged in symposium in 2017 hosted by the Center for the History of Collecting at the Frick entitled “Sculpture Collecting and Display, 1600-2000.” Of particular interest were talks on the place of sculpture in the kunstkammer by Michael Yonan and Thomas DaCosta Kaufman, as well as the papers in the “Sculpture Galleries” session, including a talk by Alison Yarrington on the country house sculpture gallery. We know that the important work done by Christopher Johns will continue to inform scholarship for generations.