Decorating the House Beautiful: Chinamania at the Russell-Cotes Art Gallery and Museum, Bournemouth

This month we feature a guest post by Dr. Anne Anderson, a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and a ceramics consultant at the Russell-Cotes Art Gallery and Museum in Bournemouth. She has been researching and cataloging the ceramics collection there since 2017. She is now working on an illustrated guide which will enable visitors to understand how the ceramics were used to decorate East Cliff Hall, originally the home of Merton and Annie Russell-Cotes. The guide will identify key pieces chosen on the basis of their quality, history or sentimental value. The publication will also mark the centenary of the opening the Russell-Cotes to the public in 1922. This post is drawn from her recent talk at the the College Art Association Conference in February 2021.

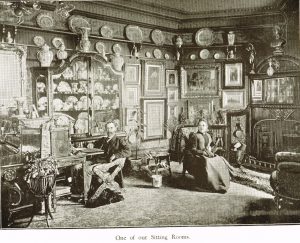

The photograph of hotelier Merton Russell-Cotes and his wife Annie in ‘one of our sitting rooms’ within the Royal Bath Hotel, Bournemouth, illustrates their passion of all kinds of ceramics: impressive porcelain vases, Oriental blue and white plates and delicate fine bone china tea wares. Two plate racks run around the room, just below the cornice, the top one carrying plates, the lower one a combination of smaller plates and vases. They are carefully spaced and graded by size. The large china cabinet is filled to bursting, with larger vases balanced on the top. Every piece has been arranged with care. Ceramics are skillfully used for their decorative effect, complementing paintings, furniture, and sculptures. As Butler Wood, a contemporary taste maker explained, porcelain’s ‘accent and sharpness’ provided a ‘counter note’ to the reticent beauty of paintings and furniture; such ‘flower-like things’ graced ‘the whole with the lighter touches of piquancy, flutter, and capriciousness… Porcelains have well been said to be the eyes of a room’.[i]

Ceramics were an integral component in Merton and Annie’s artfully composed decorative ensemble. We can admire the overall effect; the mass of different shapes and colours would have been visually arresting, if not overwhelming. The careful placing of pieces according to size, shape, and colour, creating a harmony that was pleasing to the eye, reveals a level of skill; the Russell-Cotes’s did not employ a professional decorator to orchestrate this composition. Rather the selection reflects their own tastes and interests, albeit guided by the fashions of the day. Advice manuals aimed at the middle-class homeowner, extolled the virtues of creating an individual home. The blandishments of the salesman were to be ignored, otherwise all houses would look the same. Charged with creating an original home, one that reflected a unique personality, the homeowner was empowered as an artist. Given the great variety of ceramics that could be acquired, they were a perfect means of demonstrating one’s innate taste and creative flair.

With the accent on uniqueness and rarity, antique porcelains and pottery became highly desirable. Moreover, they could not be simply bought over the counter. There was the thrill of the chase in tracking down unusual and valuable pieces. This necessitated acquiring some knowledge of important factories and distinguishing marks. For the dedicated collector and connoisseur, rarity and authenticity might supersede aesthetic appeal. Provenance, tracing previous, possibly illustrious, owners added cache to a piece, as did adding one’s own name to the lineage. Collectors were also motivated by sentimental feelings; mementos, reminders of a person, and souvenirs, recalling a place, exerted a strong emotional appeal. For all these reasons, by the 1870s collecting ceramics had become a fashionable craze dubbed ‘chinamania’ by the popular press.

Whereas many collections from this era were dispersed upon the death of the owner, the Russell-Cotes collection remains largely intact. Much was removed from the Royal Bath Hotel to Merton and Annie’s dream home East Cliff Hall. Although conceived in 1897 and completed in 1901, making it one of the last Victorian houses, the interior décor largely reflects the tastes of the 1880s. Echoing the Royal Bath Hotel, the interiors were beautified with paintings, sculptures, furniture, and ceramics. Decorator John Thomas was commissioned to paint the rooms with pictorial friezes, peacocks in the dining room and rooks in Merton’s study, reprising designs first used at the Royal Bath. Plate racks were installed in the dining room, Annie’s boudoir, and Merton’s study. China cabinets were moved from the hotel to the house, the example seen in the photograph ending up in Annie’s Boudoir. Merton apparently loved china cabinets and he had many to fill!

A close examination of the ceramics reveals much about Merton as a collector and decorator. The assemblage is remarkably diverse, comprising old and new wares, high quality porcelains and inexpensive pottery, reproductions, and even fakes. Some pieces might be categorized as ‘kitsch’ and even banished to the storerooms. But it is the blending of all these disparate components into a decorative ensemble that makes them interesting. I would argue Merton was not a connoisseur in the accepted sense; he did not form a representative, typological, assemblage or restrict himself to one factory. He did not classify his pieces by age or type. His approach was aesthetic, the priority to create displays that appealed to the eye. An impressive satinwood cabinet in the drawing room was filled exclusively with white porcelain figures. In his autobiography Home and Abroad (1921), Merton claimed he shared this admiration for white figures with Thomas H. Woods of Christie, Manson & Woods, the famous auction house: ‘He, like myself, had a great love for white Bisque china, of which he possessed a remarkably fine collection.’ [ii] For Merton, who loved to name drop in his autobiography, this shared appreciation placed him in exulted company.

Merton was so proud of this cabinet that he included an illustration in Home and Abroad. Using this I have been able to reconstruct much of the display. Although all white, the collection was not homogeneous in terms of materials or makers. The quality of individual pieces also varies, their aesthetic value only becoming apparent when the ensemble is viewed as whole. Some of the finest figures are Minton Parian ware, a type of unglazed porcelain ideal for sculpture and so named to recall the fine white marble quarried on the Greek island of Paros. Along the top of the cabinet were the Amazon Taming a Horse, Ariadne and the Panther, and Una and the Lion, which were first issued in the 1840s.

Within the cabinet, The Greek Slave, a Minton Parian figure modelled after the famous sculpture by Hiram Powers, sits on the shelf above A Cavalier, a bisque figure by Vion and Baury, Paris, modelled after Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier’s painting A Cavalier: time of Louis XIII (1861). Pandering to popular sentimental taste, the latter might well be dismissed as kitsch.

Yet A Cavalier reveals Merton’s ambitions and even exposes his pretentions. He would have loved to own a painting by Meissonier, who specialized in scenes of 17th and 18th century French life, but they were enormously expensive. With an original beyond his reach, Merton acquired a copy of Meissonier’s Le Fumeur by Reginald Ernest Arnold (1853–1938). A Cavalier (1861) was in the famed Wallace Collection, created by Lord Hertford and Sir Richard Wallace. Did Merton hope East Cliff Hall would be lauded as a modest version of Hertford House? While the Sèvres porcelain displayed in Hertford House is second to none, Merton’s admittedly modest ceramics collection is historically valuable. It offers us a unique insight into how ceramics embellished the late Victorian/Edwardian middle-class home.

[i] Sir Merton Russel-Cotes, Home and Abroad An Autobiography of an Octogenarian, Vol.2, Bournemouth: Privately printed, 1921, p. 693.

[ii] Butler Wood, ‘Art Section: Prefatory Note’, City of Bradford Exhibition Catalogue of the Works of Art in the Cartright Memorial Hall 1904, Bradford: Armitage and Ibbetson, 1904, n.p.