Frederic Leighton’s Silk Room and his Display of Fellow Artists

We are delighted to feature new research by Pola Durajska, a graduate student at the University of York. She is currently a PhD candidate at the University of York, working under the supervision of Professor Elizabeth Prettejohn. Her research project, ‘I saw Nature unfold before my eyes:’ Nature, Science, and Myth in the Landscape Art of Frederic Leighton, examines the largely overlooked open-air sketching practice of the Royal Academy President with respect to the three inter-connected themes. Her research interests concentrate mainly on Victorian art but span from the receptions of the Renaissance to interactions with nineteenth-century science and literature. For this post, she adds to the Home Subjects discussion of Leighton House, mentioned in previous posts.

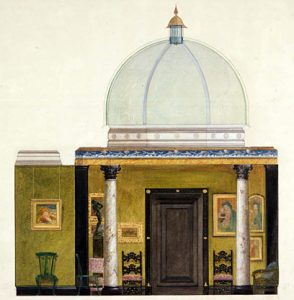

George Aitchison, Design for the Elevation of a Wall of the Picture Gallery, 1895, watercolor. RIBA Collections, London.

As the President of the Royal Academy from 1878, Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) enjoyed an immense influence on the London art world. Of no less importance was his magnificent studio-house at Holland Park Road, which had a reputation as a cultured enclave, housing a number of prominent Victorian artists and patrons. Leighton’s residence, designed chiefly by George Aitchison, was completed in 1866 but underwent several extensions throughout years. The final addition was the Silk Room, a space envisioned for the display of paintings by Leighton’s contemporaries. Like the rest of his interiors, it was widely covered by press: detailed descriptions were supplemented by reproductions of Aitchison’s original watercolour designs as well as photographs. Leighton’s house as a whole reflected the trend, started in the early 1880s, of magazines and journals featuring glimpses of artists’ homes.

As Aitchison reported in The Builder, in the 1890s Leighton realized that he needed additional space to hang “the pictures and sketches” presented to him by his fellow artists, so: another room was built over the library and adjacent to the old-painting room, the wall dividing them was removed, and its place supplied by black marble pilasters and monolithic columns of pavonazzetto with bases and carved capitals of black marble, an architrave of yellow Numidian marble, and a dolphin frieze. The new room was lit by a glass dome to match the other. A plain black marble chimney occupied the centre of the east side. The walls of the “picture gallery” were covered in “faded leaf-green silk.” The construction of the extension began in the latter half of 1894, and in March 1895 it was opened for (what turned out to be Leighton’s final) musical event. The absence of evidence for the dolphin frieze other than Aitchison’s design suggests that the Silk Room was never fully completed, possibly due to Leighton’s deteriorating health and travels abroad.

Leighton’s biographer Ernest Rhys described the Silk Room as an addition “which completes the artistic economy of the house.” Its focal point was the south wall hung with paintings presented to him by some key members of the London art world. Most notably, at its center was a large canvas by John Everett Millais, Shelling Peas (1889), flanked by G. F. Watts’s oil study for Hope (c. 1885) and Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s In My Studio (1893; discussed in this Home Subjects post). While the central canvas, dedicated to the President, seems to have a primarily representational purpose, demonstrating Leighton’s institutional affiliation through the presence of Millais (another crucial figure at the Academy who succeeded him as President), the neighboring two had more artistic potential for Leighton’s own oeuvre. Watts’ Hope is often seen by scholarship as contributing to the composition of Leighton’s Flaming June (exhibited in 1895), and that relationship is confirmed not merely by the latter’s ownership of the work, but also by the close and lifelong friendship of the two artists.

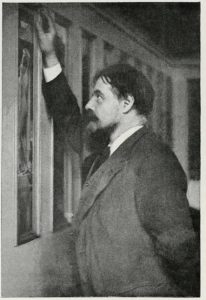

The painting by Alma-Tadema also presents an interesting case of artistic exchange, as it advertises his own lavish studio-house at Grove End Road on the walls Leighton House, a rival “Palace of Art.” Alma-Tadema’s home included the Hall of Panels, transferred from the previous “Casa Tadema” and comprising forty five tall narrow paintings by a number of fellow artists. Among them was Leighton’s The Bath of Psyche (a larger version of which he completed in 1890), which must have particularly resonated with Alma-Tadema. He was photographed admiring the panel closely over the span of many years; first in a photograph featured in the Magazine of Art in 1897 and again in a portrait reproduced in Scribner’s Magazine in 1911.

Lawrence Alma-Tadema in the Hall of Panels, published 1897. Reproduced from: M. H. Spielmann, ‘Laurence Alma-Tadema, R.A.: A Sketch,’ Magazine of Art (Jan 1897): 42-50.

In My Studio can be considered a slightly delayed, yet entirely appropriate reciprocation, potentially produced specifically with the Silk Room in mind, as Leighton began planning this addition a few years before its construction. The picture’s composition perhaps references an earlier painting by Leighton, A Noble Lady of Venice, while its setting capitalizes on promoting Alma-Tadema’s own studio and practice. Apart from subsequently completing a number of paintings including the characteristic fragment of his studio, in 1895 (the same year as the official opening of the Silk Room) Alma-Tadema was photographed in the exact same spot by the famous Berlin Photographic Company.

The case of In My Studio exemplifies a clever marketing strategy as well as embodies the artistic exchanges of the close-knit London circle. At the same time, Watts’s sketch for Hope attests for Leighton’s openness towards processing ideas conceived by fellow artists, and the impact of his artistic friendships on the development of his own oeuvre.