Tastemaker-in-Chief: Reflections on Decoration in the White House

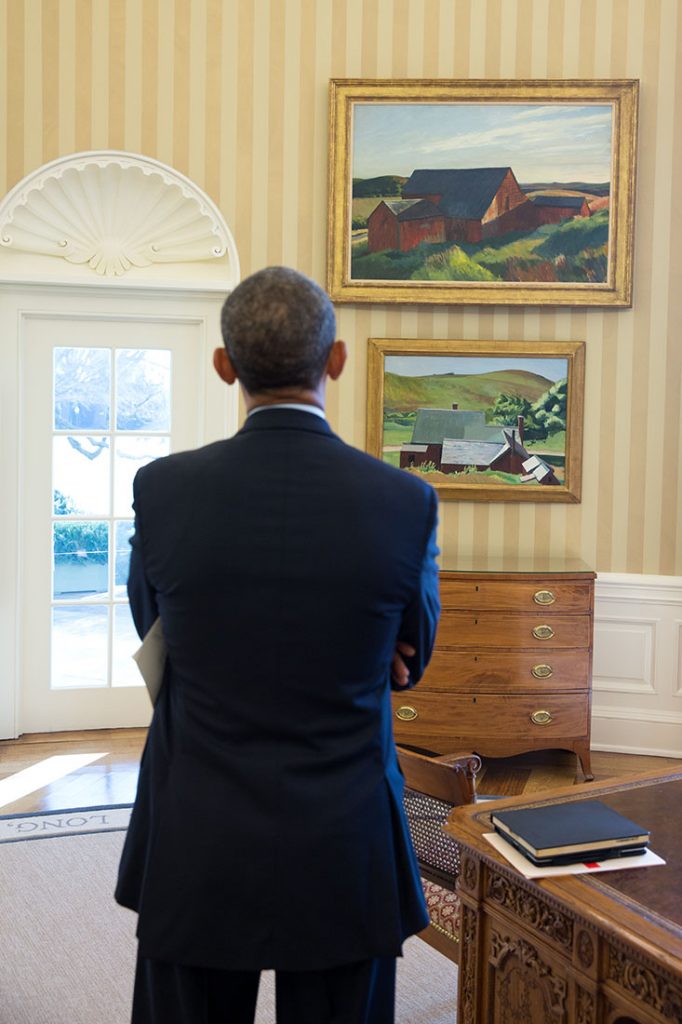

President Barack Obama looks at the Edward Hopper paintings now displayed in the Oval Office, Feb. 7, 2014. The paintings are Cobb’s Barns, South Truro, top, and Burly Cobb’s House, South Truro. (Official White House Photo by Chuck Kennedy)

At this moment of political transition, Home Subjects reflects on the role of the political residence as a symbolically-freighted site for cultural taste-making. In recent weeks, stories have appeared in a variety of media discussing the possible implications of our changing political climate on the arts, and many of these implicitly draw on the trope, in place since at least the early eighteenth century, that taste can be regarded as an index of moral character. The NPR podcast Studio 360 recently devoted an episode to POTUS as Tastemaker, an hour that highlights President Barack Obama’s oft-touted cool factor, especially in the medium of music. In the realm of visual arts, the Obamas were less involved than most of their predecessors with establishment art venues such as the National Gallery, but took the opportunity to decorate the White House with paintings by Edward Hopper lent by the Whitney Museum of American Art. The Obamas’ choice of pictures by Hopper juxtaposed a rural, Depression-era aesthetic with the canonical nineteenth-century pictures that already represented the American experience in the Oval Office. After an election in which one widely-repeated narrative holds that the Democratic party had lost touch with the very type of middle-class, rural American whose landscape appears to be represented by Hopper’s pictures, an image of Obama reflecting on these pictures may appear prescient.

Lest we think the notion of the President as Tastemaker-in-Chief a recent phenomenon, the president’s residence has long served a symbolic role. Even its name, the White House, conflates the head-of-state’s official dwelling with a house for the nation, one freighted with the weight of cultural expectations that the designation implies. The implication has been that the style of decoration implemented in the domestic interior that functions as both public and private space is a barometer of its occupant’s taste and might reflect the state of the nation more generally. In 2007, the White House Historical Association invited artist Peter Waddell to make a series of paintings commemorating important moments in the history of the residence, beginning with its construction in 1792. Waddell’s series offers an instructive exercise in imaginative historical re-creation, envisioning narrative moments at the White House as that building may have appeared in the moment in history when they took place. As contemporary versions of the nineteenth-century genre paintings that tapped into a sense of nostalgia for times past, the pictures purport to re-create both public and private events in presidential domestic history, including one of Dolley Madison’s balls and the illumination of the East Room with gas chandeliers under Ulysses S. Grant in 1873-74.

Peter Waddell, A Bird that Whistles (In Jefferson’s Cabinet, 1803), 2007, The White House Historical Association

The pictures in Waddell’s series are certainly hybrid creations, blending historical documentation of White House decorating schemes with genre to present the viewer with an impression of the past that “feels” right. Perhaps the most compelling picture in the series, A Bird that Whistles (in Jefferson’s Cabinet, 1803), incorporates objects known to have been amongst Jefferson’s furnishings in this period. Such objects as the landscape of Niagara Falls, visible at the upper right of the picture, a map of the United States prior to the Louisiana Purchase, works of natural history, globes and scientific instruments, and a few antique art objects atop the towering bookcase encourage the viewer to feel that we are actually peering in on Jefferson at work in an environment he created.

The text describing the picture on the White House Historical Association website places Waddell’s scene in the context of Jefferson’s choice to redecorate the White House after the intense, divisive campaign between Jefferson and Aaron Burr that had taken place in the fall of 1800. As the winner, Jefferson had the opportunity to remake the interior of the White House after his own vision. According to the WHHA, “from the beginning Jefferson had thought the President’s House too grand, so when it became his home he cut it down to size in use. This room, a formal levee or reception room under Adams, Jefferson converted it into his office.” Embedded in this disagreement over style and use of space appears to be an issue with more far-reaching implications, the long-standing trope that taste and style are visible indices of character and morality. As Anna Marley has written, Jefferson embraced a style of hanging pictures and displaying objects in the interior that he had seen on a tour of English country houses in 1786, and had a passion for French furniture. Jefferson’s enthusiasm for European design could be (and was) contrasted to other founding fathers’ (notably John Adams) disdain for formality and courtly ritual that signaled a kind of authentic “American-ness.” Over the course of the twentieth century and up to the present, questions about taste and decorating choices (including which pictures will be hung in the White House) have been frequently mobilized by the press in an attempt to gauge the character of the first family. Certainly, the notion that the decoration of a nation’s most important political residence should be understood as is not unique to the United States. A tour of 10 Downing Street reveals that the art displayed is similarly calculated to celebrate the convergence of British art and subjects that celebrate important moments and figures in British history. Amongst the pictures specifically noted by the linked article are a portrait of Elizabeth I, landscapes by J.M.W. Turner in the White Drawing Room, and a portrait of Margaret Thatcher in the study. After Brexit, a few writers have emphasized the changes in taste that can occur with changes of administration–the Daily Mail even obliges its readers with prices and brand names of some of Theresa May’s recent additions to the property.

The modern history of this trend could be dated to the Kennedy White House. Jackie Kennedy, a famously stylish first lady, embarked on a major restoration campaign. Images of the renovated White House inhabited by the Kennedys’ young family achieved cultural saturation after the broadcast of A Tour of the White House with Mrs. John Kennedy on all three major television networks in February 1962. Mrs. Kennedy had hired the fashionable New York interior decorator and socialite Sister Parish to redecorate the family’s rooms. Parish’s style, which was less formal than the world she was born into and tended to pair expensive heirlooms with handicrafts, has become so widely influential on American taste since the 1960s that most Americans probably assume that it is not a “style” so much as just the way things are. The style most Americans associate with the White House is Parish’s style, reflecting a particular brand of mid-century upper-class chic rather than a tradition that many might expect dates back to the late eighteenth century.

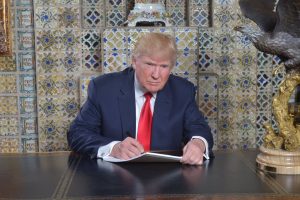

As Inauguration Day approached, the press began to address the perennial question of how the incoming first family’s tastes might imprint themselves on the historical interior. A profile of the Obamas that appeared in Architectural Digest less than 10 days before the election had described the family’s interventions as “speak[ing] volumes about the sea change in American culture the two have championed for the past eight years.” Months before the election, The New York Times had already raised the topic, citing historian Douglas Brinkley observing that Trump’s unabashed embrace of Louis XIV-style glamour runs counter to the trend in American politics since the early twentieth century to “tamp down perceptions of wealth.” People Magazine, writing immediately post-election, could only guess at what might be in store for the White House, but suggested that the building’s special status might mean that few significant changes would be made. As this post was being edited for publication, the President-Elect tweeted a picture of himself working on his inaugural address while seated in front of a backdrop of what appears to be sixteenth-century Spanish tile work and accompanied by a tabletop sculpture of a Bald Eagle in flight.

The tweet identifies the setting as the new “Winter White House”, Mar-a-Lago, but again raises the question of how the new administration might use decorative choices for political messaging (and whether those messages might at times be contradictory). It remains to be seen what other changes might await the White House with a new President and first family, but art has already become entangled in the politics of decorating the Trump administration. The St. Louis Art Museum faced criticism for its decision to lend George Caleb Bingham’s exploration of democracy entitled The Verdict of the People (1854-4) to a congressional luncheon held during Donald J. Trump’s inauguration on January 20. An artist and an art historian based in St. Louis organized a petition calling on the museum to cancel the loan: “we are concerned that the loan of the painting for the inaugural luncheon implies that our local community, and the arts community in general, support the election of Trump.” Hung in the National Statuary Hall in the US Capitol, the painting attests to what the petitioners themselves acknowledge: “art is always implicated in politics.” To that, we could add “interior decoration.”

This post was a collaboration between Morna O’Neill and Anne Nellis Richter. Home Subjects is supported by The Humanities Institute at Wake Forest University and The National Endowment for the Humanities.