From Palais Royal to Pall Mall

Editor’s note: Today we are continuing our series of posts previewing an upcoming Home Subjects panel at the conference Creating Markets, Collecting Art, which will convene at Christie’s Education in London July 14-15, 2016. Our next poster/speaker is Anne Nellis Richter, who is Adjunct Professorial Lecturer in Art History at American University, and one of the founders of Home Subjects. –MO’N

On May 7 1806, the Marquess of Stafford opened a gallery of pictures in his seventeenth-century townhouse, Cleveland House, to the public. With this act, the Marquess transformed a private aristocratic townhouse into a space which was widely understood as a public art gallery avant la lettre. The number and quality of pictures on display at Cleveland House was unlike anything available elsewhere in London at this time, its rooms filled with pictures by revered Old Masters such as Raphael, Titian, Poussin, Claude, and Annibale Carracci. A significant portion of the pictures on display at Cleveland House had come from the Orleans Collection, a collection belonging to the Dukes of Orléans that had been imported into England and sold during the 1790s. This collection was one of the most spectacular examples of French collections that were imported into England during the aftermath of the French Revolution. Upon their arrival in London, several newspapers suggested that the Orleans pictures might fill the role of a “national” collection. Cleveland House’s status, as a private house which was coming to be understood as one in which the public had a vested interest and right of access, both mirrored the circumstances under which these pictures had been exhibited in France, but at the same time was seen as unmistakably English, and in many ways, an improvement on the French system.

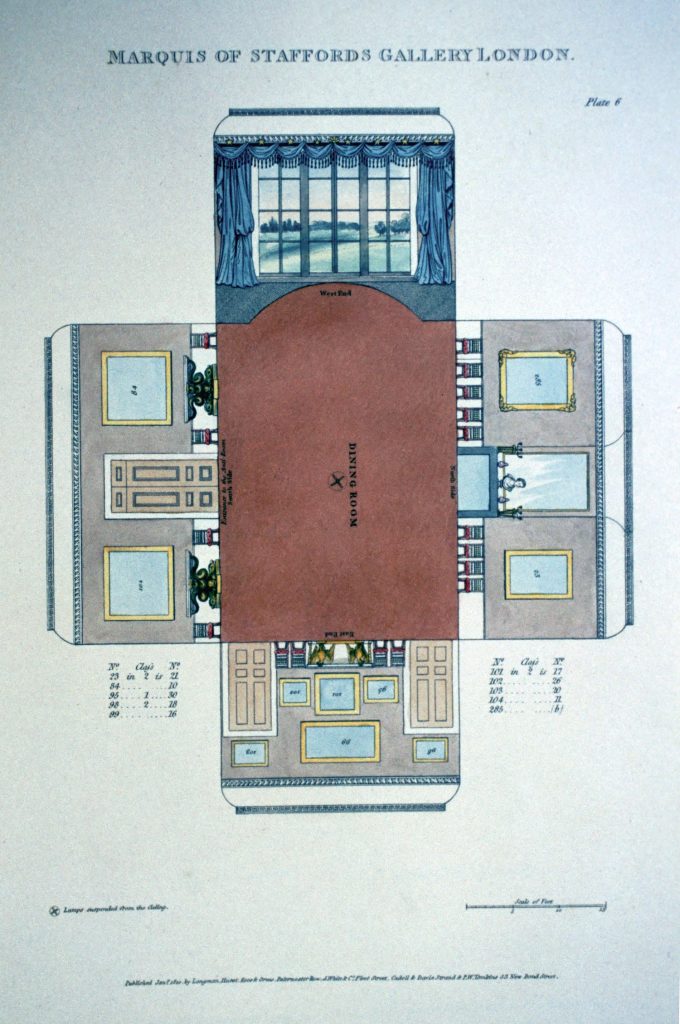

In 1806 The Times reported, “The magnificent suite of apartments which have been fitted up for the reception of these paintings consists of two grand galleries, and five other rooms. The pictures are placed to far greater advantage in Cleveland House than at the Palais Royal, or even in the Galleries of the Louvre.” It had taken less than a decade for the Orleans pictures to become widely accepted as “national” treasures, ones which were even more appropriately housed in a London townhouse than under the auspices of the French state—a status which their position in London’s most prestigious private dwellings helped to confer. An image of the Dining Room at Cleveland House indicates that Titian’s Diana and Actaeon and Diana and Callisto, both from the Orleans collection, were hung on either side of a doorway anchored by pier tables in the form of dolphins. Titian’s pictures, which at the time of their importation were so desirable because of their continental provenance and rarity in English collections, quickly came to be understood as “national” property—as early as 1806, one London magazine described the private gallery that had been constructed to display them as “a National Museum rather than [a] private collection.” The process through which pictures of foreign provenance were transformed into English patrimony has pressing contemporary significance; in 2012, Diana and Actaeon and Diana and Callisto were deemed of such importance to the British nation that they were purchased by the National Galleries of Britain and Scotland for a combined price of £95 million.

As objects, the Orleans pictures were emblematic of the shift in power in France from royalty to the “people”—their very availability on the art market had been enabled by the unleashing of violence and revolution; a process with which the name of Orleans was inextricably linked. Because the pictures’ presence in England was symptomatic of a changing international political climate, English collecting practice became politicized in response. In 1805 one observer wrote: “The commotions on the continent have operated as a hurricane on the productions of genius, and the finest works of ancient and modern times have been torn from their old situations. Many, very many, of them have been consigned to this country, and are now in the private collections of our nobility and gentry, in and about the metropolis.” Using the metaphor of a “hurricane”, which suggests a natural rather than a man-made disaster, this writer softens the political and human drama of these events to a remarkable extent. Such metaphorical language spares the reader any direct confrontation with the knowledge that the “tearing” of such artworks from their former situations had been accomplished through the means of Revolution and war—not to mention the sale of collections by those who were already in a state of distress or who feared the seizure of their property by the government. There has been much fascinating and important work done on both the art sales of the 1790s generally and the Orleans Collection specifically; the purpose of this talk is to explore how the workings of the art market, and in particular the different strategies deployed to exhibit these pictures to members of the public, participated in the process of transforming pictures like these from French national treasures to English ones. I will consider how these pictures were exhibited from the time they left the walls of the Palais Royal, a private palace where they had long been on display to a polite public, to Pall Mall, where they were exhibited in the context of a commercial showroom, to Cleveland House, where they were subsumed back into another kind of private space, one which, like the Palais Royal, exhibited pictures in an environment which imposed no clear boundary between public and private space.