Originals and Copies

Thomas Lawrence, Portrait of Lady Elizabeth Foster, later Duchess of Devonshire (1759-1824), c.1805, Oil on canvas, 240 x 148 cm, Bequeathed, Sir Hugh Lane, 1918, National Gallery of Ireland, NGI.788

Scholars interested in the display of art in the domestic interior often turn to representations of those interiors as source material for understanding the decorative scheme, the arrangement of furniture, and the disposition of works of art. For a long time, it never occurred to me that some of the works of art given pride of place in a family’s house might be copies. It is well known that collectors often obtained copies of revered masterpieces. The pictures of which I write here are different: these copies that were generated in the course of a financial transaction in which owners might sell an original artwork in their possession and hang a copy in its place. Frequently such a route might be taken when owners sold works of art that were particularly significant to their family of origin or to the interior in which they were displayed. The possibility that owners might adorn their walls with copies of originals dispersed elsewhere raises a fascinating set of issues that we need to consider when thinking about the display of art in the domestic interior. Let me give an example.

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Polish Rider, ca. 1655, Oil on canvas, 46 x 53 1/8 in. (116.8 x 134.9 cm), Henry Clay Frick Bequest, Accession number: 1910.1.98

In the late spring and summer of 1910 American industrialist Henry Clay Frick was making arrangements to acquire Rembrandt’s Polish Rider from the collector Zdzisław Tarnowski. Tarnowski was a landowner, industrialist, and politician, who lived in Dzików Caslte in Tarnobrzeg in the Galicia region of Poland. The Tarnowski family had amassed an art collection that included not only Rembrandt but also works by Titian and Rubens as well as Polish artists like Jan Matejko. By 1910, however, the family began to sell select works.

The correspondence surrounding this transaction reveals the significance that copies could play in the study of such artworks, and raises questions about why such copies might be acceptable to the picture’s former owner. In a letter to Henry Clay Frick dated April 24, 1910, English art critic Roger Fry, who had helped arrange the sale, noted that the deal included a copy and that the painting would be taken to the Carfax Gallery in London while the copy was prepared. In a second letter, from July 6 of that year, Fry updated Frick on the copying process: “the Rembrandt copy is just finished or will be in a day or two, the artist has worked very hard at it, getting to work at 6:00am.” Fry suggests that the process of copying revealed new insights about Rembrandt’s technique: “But although the picture has a general air of broad and rapid handling, one finds this is deception and that in reality the figure of the rider is finished with a quite overwhelming sense of detail which is yet so subordinated that it never catches the eye until one proceeds to a minute examination.” The challenge of copying, then, is to match the level of detail yet keep it “subordinated” to the whole. Fry refers to the copyist as Mr. McEvoy, and it is possible that he means Ambrose McEvoy (1878-1927), who trained at the Slade and was affiliated with the New English Art Club. According to Fry, McEvoy “thinks [The Polish Rider] far finer than the National Gallery Rembrandt which he copied.”

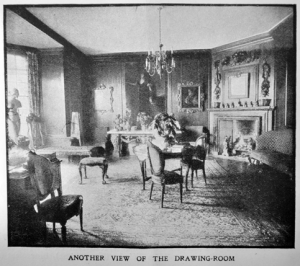

Lawrence’s portrait of Lady Elizabeth Foster hanging in the Double Drawing Room at Hugh Lane’s residence, Lindsey House, London, c. 1909, from The Graphic.

This scenario raises some fascinating questions for those of us considering the display of art in the domestic interior, and initial archival research suggests that it was not an uncommon scenario. Sir Hugh Lane purchased Thomas Lawrence’s Portrait of Lady Elizabeth Foster (c. 1805, National Gallery of Ireland) from Sir Vere and Lady Foster of Glynde Castle, County Louth, and the arrangements included a copy of the painting to hang in the place of the original. As Lane explained to another potential seller, “If you thought of selling the picture I know of a wonderful copyist who could make you so perfect a copy of it which you could hang in the original frame now on your picture and which would be so like the original that no one except a few experts on close examination could tell the difference.” This provides a unique point of view of the work of art in the age of (non-mechanical) reproduction. For the aristocratic seller, a Lawrence or a Gainsborough portrait of a venerable ancestor was an object of cult value in Walter Benjamin’s terms. Paradoxically, however, authorship was unimportant: they valued the painting for what it represented and would accept a copy in place of the original. Like a photographer’s negative of a family portrait, a Lawrence or a Gainsborough could be copied for those who cared more about the subject matter than they did the personal touch of an acknowledged master of the genre.

Yet the presence of a copy rather than the original could lead to awkward situations. As Lady Vere Foster confessed to Lane, “if you only knew the tribulation I go thro’—how I squirm and feel worse than in a dentist’s chair when people admire the Lawrence! I always walk away at once.” Lady Vere Foster is caught in a trap: she cannot acknowledge that her Lawrence is not the Lawrence, yet, by walking away, she suggests to visitors that she does not appreciate an art treasure in her own home.

These copies remind us that a copy is not always a forgery. According to art historian Alexander Nagel, “the emergence of art forgery presupposes a culture in which what matters above all is not the content a work of art transmits but the irreducible qualities that make this work an unrepeatable event.” Early modern collectors frequently privileged a copy of a known work over the unknown original, suggesting that the imagery or the association of the subject was prized above the originality or authenticity of a work. We may speculate that the Tarnowskis wanted a copy because they valued the way that the work of art decorated their interior. At the very least, it asks us to consider the possibility that some works of art were intended as decoration, even if they were painted by Rembrandt. For the Vere Fosters, they retained the image of their ancestor. Second, it suggests that the art market would later turn many a copy into a forgery. For the Tarnowskis and the Vere Fosters, the copy was acceptable as a copy, but for outsiders, and for subsequent owners, the copy would appear as a forgery. By 1910, the long-standing artistic tradition of copying and imitation was replaced by a new paradigm of originality and invention, one privileged by the art dealer’s own business model.

–MO’N