Finding Room for Art: William Orpen’s Portrait of Sir Otto Beit (1913)

Harvard Art Museums is planning a symposium that may be of interest to the Home Subjects community: “The Room Where It Happens: On the Agency of Interior Spaces.” This event will accompany the exhibition entitled “The Philosophy Chamber: Art and Science in Harvard’s Teaching Cabinet, 1766-1820.” In addition, the Frick Collection and the Furniture History Society recently invited submissions for an emerging scholars program on “Furniture and the Domestic Interior.” These events both call to mind the importance of the room as a space of display. In these contexts, the room become what architect Robin Evans referred to as “a particular area of human affairs,” one that was often “enmeshed in a nexus within which the social activities and proclivities of [the] client were prominent.” The idea of a room as a space for human affairs calls to mind the recent “spatial” turn in art history, an approach that can draw out a rich series of connections when we consider the depiction of a room–and the display of art within it–in a painting, as in William Orpen’s Portrait of Sir Otto Beit (1913, now in the Johannesburg Art Gallery).

Spatial art history moves beyond a “center” and “periphery” model to locate cultural sites of modernism. And we might even produce micro-geographies that attend to spaces within a city or rooms within a gallery. Andreas Huyssen has argued that modernism “cuts across imperial and post-imperial, colonial and decolonizing cultures. It was often the encounter of colonial artists and intellectuals with the modernist culture of the metropolis that supported the desire for independence and liberation.” Yet modernism did not always cut across imperialism. It could also be co-opted by it and embedded within it. And Huyssen qualifies his own call for a global understanding of modernism, one that must be attentive to “cultural intermingling, appropriations, and reciprocal mimicry.”

Works of art could become symbols of a global colonial network through their exchange, and plotting the movements of works of art within this network reveals this process. As Fredric Jameson points out in his essay “Cognitive Mapping,” life as it is lived, what he calls “the phenomenological experience of the individual subject,” is both located in a place, like London, as well as “bound up with the whole colonial system of the British Empire that determines the very quality of the individual’s subject life.” That is to say that Cape Town or Dublin, or Kingston or Delhi, are “structural coordinates” for a life lived in London c. 1900. For Jameson, global colonialism was determined by capitalism and the flow of goods and services, including works of art. Figures like Otto Beit and William Orpen were central to this process, as the movement and transfer of works of art maps a history, as well as a geography, of taste in the early twentieth century.

Otto Beit was one of the principles in Werner, Beit, and Company, who developed gold and diamond mining in South Africa. His older brother Alfred Beit was also an avid art collector and supporter of the arts. While Alfred took the lead in the family businesses, Otto devoted his time and energy to collecting, and after Alfred’s death in 1906, he managed his brother’s estate and bequests. Like his brother, Otto Beit sought to fill his London townhouse and his English country estate with Old Master painting. But he was also a significant donor to the Johannesburg Art Gallery and its collection of modern art.

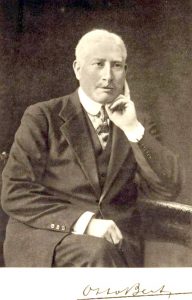

William Orpen’s portrait of Beit in his study in Belgrave Square (1913, Johannesburg Art Gallery) suggests as much. The art dealer Hugh Lane suggested the portrait commission and facilitated the arrangements. Although Beit would later complain that the portrait was not a good likeness, his presence in the painting’s foreground is almost beside the point. The real focus here is his richly decorated study in fashionable Belgrave Square.

The six oil paintings that hang behind him depict the parable of the prodigal son by the Spanish Baroque artist Bartolomé Estaban Murillo (now in the collection of the National Gallery of Ireland) and the bookcases are stacked with colorful—and expensive—leather bindings. These and the other bibelots were acquired with the wealth gained from mining in South Africa. Beit’s contented gaze at the viewer from his richly appointed study allows the room to become a kind of allegory of empire: the transformation of raw material from South Africa into wealth, status, and privilege in London.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, “The Return of the Prodigal Son,” 1667/1670 oil on canvas. National Gallery of Ireland.

Life in London, therefore, is always already about life in Johannesburg. For Jameson, these “new and enormous global realities are inaccessible to any individual subject or consciousness.” Not even Queen Victoria herself, in Jameson’s example, could conceptualize or “cognitively map” this new mode of experience. It remained “unrepresentable.” Yet this global colonial network was nevertheless figured in symbolic ways. This transference provides one way in which to reevaluate how a work of art signifies empire, as imperial wealth is everywhere and nowhere in Orpen’s portrait of Beit. Mining in South Africa created the wealth on display, but the selection of objects does not betray its origins. Orpen’s painting–and Otto Beit’s study–seem to anticipate Jameson’s notion of the symbolic figuration of what is otherwise unpresentable. It underpins everything and yet is represented only in the display of wealth, including the paintings by Murillo.