Ghosts in the Mechanism: Knebworth House and the Art of Copying

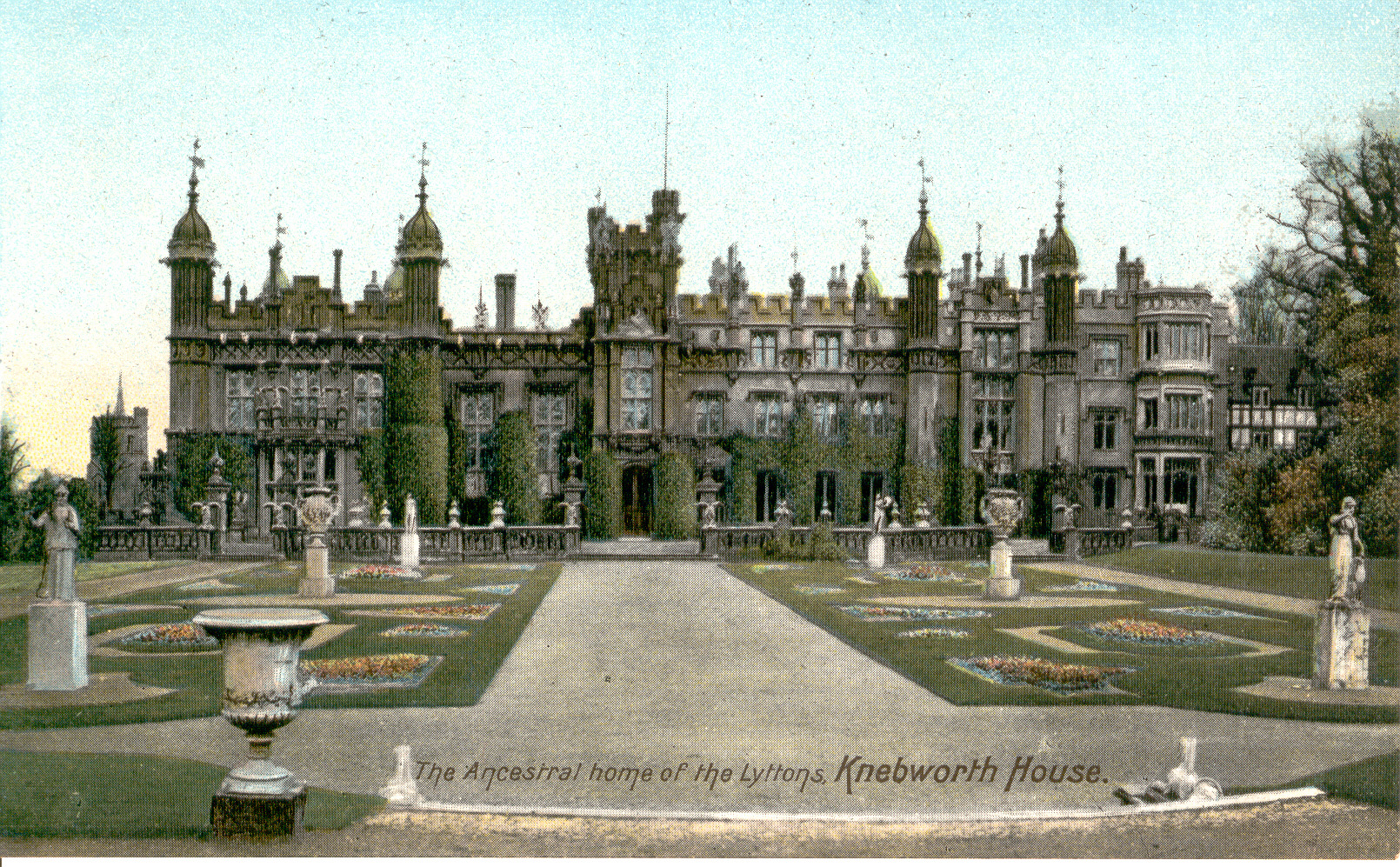

“The Ancestral Home of the Lyttons, Knebworth House,” tinted postcard, 20th century, Hertford Museum.

According to “Mysterious Britain,” Knebworth House in Hertfordshire is haunted by four ghosts. The “radiant boy” is the ghost of a child whose appearance foretells a rise to power but also death, while “Spinning Jenny” is the specter of a young woman who works at a spinning wheel. Knebworth House’s autumn programming leans into Halloween as a theme, but most activities are geared towards children and don’t mention the hauntings. While the house doesn’t appear on a recent list of “Most Haunted Places in Britain,” it does provide another opportunity to think about the domestic interior and the ghost story through its most famous resident and third ghost: the politician and author Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803-1873). Alas, space does not permit me to discuss the later reinvention of Knebworth as a music venue, but I recommend this spirited overview and classic footage of Oasis from 1996, as seen in the recent “Oasis Knebworth 1996” documentary.

Graphic from the Charles M. Schulz Museum for “It was a Dark and Stormy Night” exhibition, © 2025 Charles M. Schulz Museum.

Moving from Romantic poet in a Byronic vein to a prolific historical novelist and dramatist, Bulwer-Lytton also served in Parliament. While historical works such as The Last Days of Pompeii secured his reputation, he is also known for coining the phrase “it was a dark and stormy night,” in the novel Paul Clifford (1830). He was made a Baronet in 1838, and he inherited his maternal grandmother’s estate Knebworth in 1843 (he was later created 1st Baron Lytton, in 1866). The property dated back to 1490, with most of the house constructed in the 1560s. He remembered arriving at Knebworth House for the first time in his memoirs, and how it informed the “spirit of romance” in his novels: “How could I help writing romances when I had walked, trembling at my own footsteps, through that long gallery, with its ghostly portraits, mused in those tapestry chambers and peeped, with bristling hair, into the shadowy abysses of the ‘secret chamber.” The “secret chamber” was also called “the hell hole” accessed from a trap door in the floor.

Most of the old house was demolished by 1813, when Elizabeth Bulwer Lytton (Edward’s mother and the fourth ghost) decided that the building was “old fashioned and too large” and demolished three sides of the original four-sided Tudor courtyard house, including a medieval gatehouse. The house was reduced to just its west wing, which was then remodeled by the architect John Biagio Rebecca. The entrance gateway that stood in the center of the east side of the courtyard, which was the last remaining piece of the original Tudor structure, was eventually demolished as well. Plans and sketches made before demolition suggest the house had been altered during the 17th and perhaps 18th centuries before this major destruction. By the time the demolition was complete, no detail of the 16th century remained except for tablet bearing the family’s coat of arms. Thus the atmospheric elements Bulwer-Lytton remembered from his youth were all destroyed before he inherited the property in 1843.

His subsequent Gothic Revival transformation with John Gregory Crace was essentially decorating what was already a Regency-era remake of the original Tudor house. Most notably, the author himself designed a new staircase with Crace and the architect H. E. Kendall: a double flight of oak stairs with tall windows and ample room for his armor collection. The new State Drawing Room was Crace’s masterpiece, with an elaborate heraldic ceiling that celebrated the Lytton ancestry. A frieze featured family arms that traced their descent to Edward III and the Welsh king Cadwalladr, while a stained-glass window linked the family to Henry VII.

He leaned into the history of the home with the Queen Elizabeth Bedroom. Elizabeth I visited Knebworth at least three times, although it is unlikely that she slept in this bedroom. The idea of an authentic “historical style” here is layered and complex: while the oak four-poster is a 19th century composite of various historical beds, the room features Elizabethan paintings, and wood paneling is Jacobean. (The Jacobethan-style ceiling was a 20th-century addition.) There is one part of Knebworth that did not get a Gothic makeover: the bedroom of Mrs. Bulwer-Lytton.

At her son’s request, it was left as she had it decorated in the early nineteenth century, with a cream, pink, and gold color scheme. According to a local tourism guide, “many visitors to Knebworth have experienced powerful and unpleasant sensations in the room, which is used as a guest room for particularly brave souls. On one occasion a family friend awoke with the feeling of hands around her neck, as if someone was trying to strangle her.” If Queen Elizabeth I had a bedroom reserved exclusively for her use, so should Mrs. Bulwer-Lytton.

Accounts of run-ins with the Radiant Child go back to the early eighteenth century, while Spinning Jenny’s room is listed on a floor plan for the early nineteenth century. But what of Bulwer-Lytton’s ghost? During a 2010 appearance on Desert Island Discs, David Lytton Cobbold, 2nd Baron Cobbold (1937-2022), the author’s great-great-great grandson, said that he had heard and felt the presence of the author, while his wife saw the spectre moving through the rooms. Certainly, the Tudor Gothic décor evokes a world of passion, and spiritual depth still suited to the author’s interests. Bulwer-Lytton’s kept a crystal ball in his study, into which he was said to gaze in search of inspiration. He hosted the French occultist Eliphas Levi at Knebworth on several occasions, and the famous medium Daniel Dunglas Home held a séance there. There are also two concealed doors in the library, which may have aided the appearance of spirits in the séance. Throughout the 1840s and 1850s, he explored his fascination with mesmerism and the belief that “animal magnetism” flowed through all living things and could be manipulated through the novella “The Haunted and the Haunters: or, the House and the Brain” (first published in 1857, later edited and reprinted in 1859), considered a pioneering work in the ghost story genre.

If Bulwer-Lytton’s ghost still haunts the interiors at Knebworth House, then it is a fascinating coda to his exploration of spectra phenomena in the “The Haunted and the Haunters.” A skeptical narrative resolves to spend the night in a supposedly cursed house in London to investigate. Throughout the night, he experiences terrifying manifestations—moving objects, ghostly presences, and oppressive dread. He discovers that the disturbances are connected to a sinister figure dabbling in occult forces and mesmerism rather than traditional ghosts. Hauntings can arise from dark influences of the living as much as from the dead. The interior of the house is described as simple and old-fashioned, but with odd touches, such as cupboards without locks and a secret room. A miniature portrait of a “peculiar face” comes to play a crucial role in the plot, emphasizing the house’s age and mystery. It is tempting to imagine Bulwer-Lytton gazing into his crystal ball, imagining the outline of the plot as the Radiant Boy passes through the Queen Elizabeth bedroom.

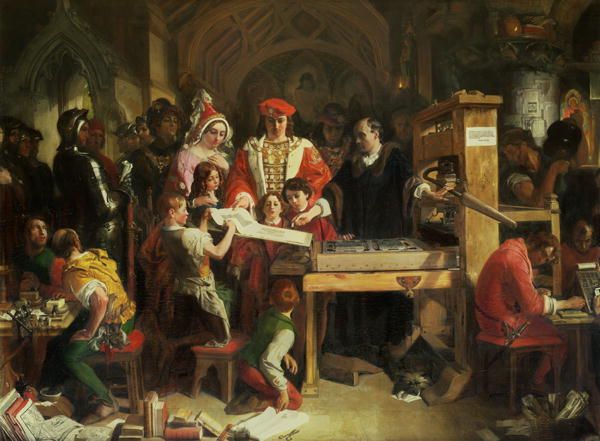

Daniel Maclise, “Caxton Showing the First Specimen of His Printing to King Edward IV at the Almonry, Westminster: With Edward are his wife, Elizabeth Woodville, and their children, Elizabeth, Edward, and Richard,” 1851, Knebworth House.

And yet, according to an article by literary scholar Bruce Wyse, Bulwer-Lytton deliberately frustrates conventional narrative expectations by presenting fragmented, meaningless spectral phenomena that resist interpretation. The protagonist’s rationalist approach treats the supernatural manifestations as mere “simulacra” produced by a mechanical apparatus (referred to as a “brain” as well as a “battery) rather than meaningful spiritual presences. Wyse connects the story’s “mesmeric machinery” to Thomas Carlyle’s critique of mechanical literary production where “Paternoster-row mechanism” and “huge subterranean, puffing bellows” churn out books as if by machinery. (One wonders what Carlyle would have made of AI?) The haunted house becomes a metaphor for the publishing industry. Ghostly manifestations of recycled literary conventions are nothing more than Gothic tropes mechanically reproduced for mass consumption. Through this machinery metaphor, Wyse argues hat Bulwer-Lytton uses the ghost story to critique the commodification of literature. Perhaps this explains why the Lytton family purchased Daniel Maclise’s painting Caxton at his Printing Office (1851) in 1876.

The painting was originally exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1851 and soon after entered the collection of John Forster, a friend of Charles Dickens as well as the artist. As young men in the 1830s, they were part of a literary and artistic social circle that included Edward Bulwer-Lytton. After Forster’s death, the painting was acquired by the Lytton family, who may have been drawn to the celebration of a significant figure in English literary history as well as its connections to the work of Edward Bulwer-Lytton. He published “The Caxtons” in 1849, in which the titular family were descendants of William Caxton. In 1850 he had hosted at Knebworth three performances of Ben Jonson’s Every Man in His Humour played by an amateur theatrical company led by Dickens and Forster. Maclise had been invited by Dickens to join the cast but had refused. The painting now hangs in the State Drawing Room of Knebworth House.

Combined image of carte-de-visite portrait of Edward Bulwer-Lytton, c. 1850 (rotated so that the profile faces the same way as the painting) and detail of Maclise’s “Caxton.”

In Caxton at his Printing Press, Maclise engages directly with technological revolution and how it can change the very structure and organization of life. William Caxton introduced the printing press to England in 1476, marking the shift from manuscript culture to mechanical reproduction. The artist depicts Caxton in his workshop in Westminster, preparing proofs for The Game of Chess for Edward IV and his court. Edward is accompanied by his wife Elizabeth Woodville, his children, and Richard, Duke of Gloucester. To the left, we see the Abbot of Westminster. Scenes from the life of famous scientists and inventors (these were also popular subjects painted by Ford Madox Brown and William Bell Scott) abound in the Victorian period. For treatment and subject matter, Maclise proclaimed his debt to The Last of the Barons by Bulwer-Lytton, who is depicted as Anthony Woodville, 2nd Earl Rivers, a friend and protector of Caxton, in the painting. Although I have yet to make a definitive identification, it would seem that Lord Rivers stands behind his sister (also the Queen) Elizabeth Woodville. In looking at portraits of Bulwer-Lytton from around 1850, it became clear to me that the figure of Lord Rivers has the same long nose. An Art Journal article from 1860s quotes Bulwer-Lytton’s own his description of the painting, noting the monk “with his scowl that is fixed upon the Book-diffuser”, the “sombre, musing face of Richard Duke of Gloucester”, the “troubled gleam in the eyes of the artisan”, “King Edward, handsome . . . delighted in the surprise of a child with a new toy”, and “Caxton himself, calm, serene, untroubled, intent solely upon the manifestation of his discovery.”

The RA Summer Exhibition of 1851 is perhaps best remembered for its strong display of Pre-Raphaelite painting and the savage response of critics. For example, the London Times conjectured that such paintings were the result of a “strange disorder of the mind or the eyes,” with “absolute contempt for perspective and the known laws of light and shade, an aversion to beauty in every shape, and . . . seeking out every excess of sharpness and deformity,” as seen, for example, in John Everett Millais’s The Woodman’s Daughter on display in the North Room at the exhibition that year. In contrast, Maclise’s Caxton was considered a highlight of the exhibition, with its “amazing industry of detail.” Throughout his career, however, Maclise faced criticism for the imaginative inaccuracies of historical subjects. Not unlike the Tudor Gothic at Knebworth, Maclise invented a past that suited the Victorian present. Although the painting looks like verisimilitude, it is an imaginative exercise. In a sense, the display of the painting at Knebworth connects the interior to the ghost story: the printing press represents the first major “mesmeric machinery” of textual production. Like Bulwer-Lytton’s haunting apparatus, the printing press generated “simulacra” – mechanically reproduced texts that were copies without originals in the manuscript sense.

The State Drawing Room, Knebworth House. Maclise’s “Caxton” hangs on the wall to the right of the mantel. Image copyright Lytton Enterprises Ltd.

The presence of Maclise’s Caxton at his Printing Press in Knebworth’s State Drawing Room creates a striking dialogue between past and present, authenticity and reproduction, haunting and machinery. Just as Caxton’s press transformed singular manuscripts into multiple copies, Bulwer-Lytton’s Gothic renovations transformed Knebworth into a theatrical stage for an imagined medieval past—one that never quite existed but felt more real than historical accuracy could provide. This layering of reproductions—Tudor Gothic overlaying Georgian, which itself had replaced genuine Tudor architecture—mirrors the very critique Bulwer-Lytton embedded in “The Haunted and the Haunters.” If ghostly manifestations are merely simulacra produced by mesmeric machinery, then perhaps Knebworth’s Gothic interior is a similar apparatus: generating the feeling of antiquity through mechanical reproduction rather than authentic survival. The three ghosts who allegedly haunt the house become part of this machinery, spectral special effects in the author’s carefully curated domestic theater.

Yet the genuine power of both the house and the story lies precisely in this self-aware artifice. Bulwer-Lytton understood that mechanical reproduction—whether through printing presses or Gothic Revival architecture—doesn’t diminish meaning but transforms it. The simulacrum becomes its own reality. Visitors to Knebworth today experience a Victorian author’s dream of the Tudor past, haunted not by medieval ghosts but by nineteenth-century anxieties about authenticity, commodification, and the industrialization of culture. If Bulwer-Lytton’s ghost still walks those Gothic corridors, he haunts a house that was always already haunted by its own self-conscious performance of history—a perpetual motion machine of spectral reproduction, still running nearly two centuries after he set it in motion.