The Long Eighteenth Century’s S-Shaped Shadow

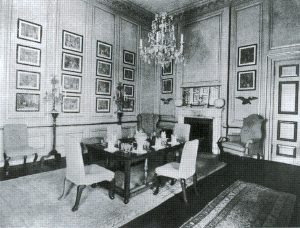

Yellow Room at Brook Street, London, where design firm Colefax & Fowler also located its headquarters. Photo credit Simon Upton/The Interior Archive.

Today’s post comes from Stephen Hague, Associate Professor of History at Rowan University. Hague is the author of several books; readers of Home Subjects will be particularly interested in The Gentleman’s House in the British Atlantic World, 1680-1780 (2015) and At Home in the Eighteenth Century (2022), co-edited with Karen Lipsedge. –ANR

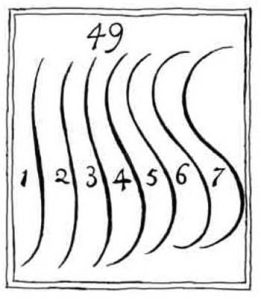

William Hogarth, ‘Serpentine lines,’ from The Analysis of Beauty (London: J. Reeves for the author, 1753).

One of the foremost arbiters of twentieth century taste, Nancy Tree, or Nancy Lancaster as she is sometimes known, created the “English country house look” at houses like Kelmarsh Hall and Ditchley Park. By looking back to the eighteenth century, Tree engaged in a process that re-imagined the past for the twentieth century. Such repurposing of eighteenth-century design speaks to what I call the long S-shaped shadow of the long eighteenth century comprised of two parts: William Hogarth’s line of beauty and the institution of slavery. These two elements of the eighteenth century – beauty and enslavement – intertwined to cast a long shadow. We simply cannot tell one story without the other.

Nancy Tree’s interiors developed over the course of buying, renovating, decorating, and living in a series of eighteenth-century houses. She set out her design ideas first at Mirador, the red brick house in Virginia where she grew up. Her process updated the décor and modernized mechanical systems, always striving to balance taste and comfort, nostalgia, and modernity. With her renovations, she attempted to conjure a sense that “it hadn’t been decorated at all, just lived in.” Her search for beauty spoke to her desire in the twentieth century to create what she called, “a comfortable environment.” To accomplish this, she crafted design rules that emphasized personality, appropriateness, scale, color, understatement, and nostalgia. Three ‘tricks’ conveyed a sense of age and historicity: open fires, candlelight, and masses of flowers. Although intended to conjure the feeling of the eighteenth century, “authenticity was not the object.” The English country house look mixed antique furnishings, old textiles, faded colors, and walls well hung with pictures to achieve interiors with a well-worn, layered, always been there, look. She described this process as “a bit like mixing a salad.” (All of these strategies are in evidence in the famous ‘Yellow Room’ that Lancaster assembled in the 1950s at her house at 39 Brook Street, London, illustrated at the top of this post.)

Of her houses in England, she loved the first one she lived in, Kelmarsh Hall in Northamptonshire, most of all. The interiors at Kelmarsh combined American and English approaches. In the Chinese Room, Nancy installed hand-painted eighteenth-century Chinese wallpaper acquired from a country house in Norfolk, a practice more in keeping with American taste at the time. For the Library she commissioned the New York architect who had worked on Mirador, William Delano, to design the paneling. This room contained a series of “odd-shaped but very comfortable chairs” covered in fabrics as various as leather, linen, chintz, and silk.

Perhaps her most significant challenge and greatest achievement was at Ditchley Park. She called Ditchley “not at all my type of house…much too grand and formal,” but nevertheless created a tasteful, comfortable, liveable space. She used the architectural features of each room as she found them while adding her own flash of inspiration. The Great Hall’s chimneypiece portrait of the builder, the 2nd Earl of Lichfield, inspired reupholstery using his coat’s crimson colour to inject energy into an otherwise formal and imposing room. In the Saloon, she scraped away paint layers to reveal the orange colour that she used on the walls while retaining objects like the blackened stag’s heads that had been in the room for two centuries.

The Breakfast Room at Ditchley hung with Hogarth prints and furnished with “old walnut chests, chairs, and tables” was a “charming room” that hinted at her colonial American roots. Yet Nancy Tree’s American origins brought with them a more complicated and even sinister side. Her Virginia house, Mirador, served as a model for her design ideas, but also highlighted the legacies of slavery and race. At Mirador she constructed a fanciful adaptation of eighteenth-century socio-economic relationships, perpetuating an elegant but fictional world that combined eighteenth century design and racial attitudes. Like her predecessors in the eighteenth century, Nancy Tree used black bodies as decoration. In the Saloon, illustrated above, she placed Moorish busts with “marvelous black marble faces, mother-of-pearl eyes and wore yellow coats” on either side of the garden doors. (Unfortunately no photographs or other images have come to light depicting the busts in situ.)

Likewise, in June 1937, at an enormous party to celebrate Ditchley’s restoration, the house was fully lit, and an enormous marquee stood covering the terrace. Inside the tent, guests confronted “papier mâché busts of negroes” dressed in fantastic costumes “perched up on marble painted columns.” With its magnificent Palladian architecture and beautiful interiors overlooked by omnipresent black figures, Ditchley simultaneously illustrated the light and dark of the long S-shaped shadow of a reinterpreted long eighteenth century. By using the eighteenth century for contemporary design, Nancy Tree’s work mixed beauty, class, gender, nationality, and race to draw together two centuries on several levels.