A Book of Architecture: Circulating style in the 18th century

Furniture made c. 1759 by Thomas Chippendale for the Blue Drawing Room at Dumfries House. Photo courtesy of Dumfries House Estate via Google Arts & Culture.

Until 1754, Thomas Chippendale had been an obscure cabinetmaker living in London’s St. Martin’s Lane. Then he published The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director, an ambitious collection of furniture designs that became a runaway success, both at home and abroad. Even today, who does not recognize the name Chippendale? Not only did Chippendale’s name become practically synonymous with the style of his furniture, but, as a catalog, the Director completely recalibrated the cabinetmaker’s professional relationship with his clients. The print and the illustrated book allowed artists like Chippendale to advertise their work directly to the eager public, and, by consolidating that work into a series of engraved images, it also allowed that public to choose their favorite chairs, bookcases, and tables with which they might furnish or refurnish their interiors in the newest and latest taste.

Parlour from 11 Henrietta Street, c. 1727-1732, described as the only surviving example of a townhouse interior designed by architect James Gibbs. Victoria & Albert Museum.

If Chippendale and his catalog remain famous, the Director was not especially groundbreaking. More than two decades before, in 1728, the architect James Gibbs published his own professional catalog, A Book of Architecture Containing Designs of Buildings and Ornaments. Gibbs’s book was unique. It was the first English architectural book to contain only designs by its author. In a series of 150 engraved plates, the Book of Architecture presented a broad and varied showcase of Gibbs’s architectural accomplishments up to that point, including the renowned St Martin-in-the-Fields (completed 1726). In addition to the exclusive use of only his own designs, another unique characteristic of Gibbs’s book was its scope. It presented a great variety of building types, from country houses and suburban villas, to public buildings, churches, and garden pavilions. But it also included a large assortment of ornament, including coats of arms, chimneypieces, windows, cornices, doorcases, columns, niches, balusters, vases, cisterns, tables, and pedestals.

Three designs for doorcases, plate from A Book of Architecture, Containing Designs of Buildings and Ornaments, by James Gibbs (London, 1728)

While the sheer variety of designs in Gibbs’s book is almost overwhelming, his compositions, which group like designs and arrange them neatly into rows for comparison, visually confirm that he is offering a selection of preapproved stylistic options available in numerous typologies, much like Chippendale’s Director would do two decades later. This is particularly evident in the plates of ornament which make up the second half of the Book of Architecture, such as the five plates of designs for chimneypieces. Each plate contains eight individual designs arranged in four rows of two. This clean and efficient compositional strategy also groups the chimneypiece designs into a series of pairs, each of which appear to be variants of one another.

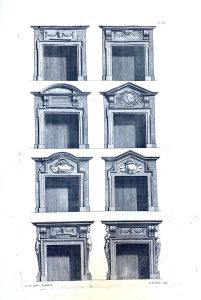

Eight designs for chimney pieces, plate from A Book of Architecture, Containing Designs of Buildings and Ornaments, by James Gibbs (London, 1728).

In Plate 93, the uppermost pair of chimneypieces offers two different designs for festoons, the pairs in the second and third rows give a segmental arched pediment on the left and a triangular pediment on the right, with various options for carved or uncarved aprons beneath. Similarly, the lowermost pair offers two designs for chimneypieces supported by caryatids, male on the left and female on the right. Significantly, the two designs on each row share a ground line which, whether intentional or not, further unites them as a pair of options. In much the same way, Gibbs’s designs for doorcases are compositionally arranged as variations in several styles, such as Plates 101-107, offering designs from the restrained to the exuberant.

In many ways, Gibbs’s comparative plates of designs in the Book of Architecture seem to anticipate those used two decades later by Chippendale in the Director, and certainly the Book of Architecture served as a model for Chippendale’s book. Like Gibbs, Chippendale presents a wide array of designs and frequently arranges them in compositional groupings very similar to the plates in Gibbs’s Book of Architecture. Also like Gibbs, Chippendale groups his plates by types, and often into further groups in the explicitly stylized terms “French,” “Gothic,” and “Chinese.”

Thomas Chippendale, preparatory drawing for Plate 16, “Ribband Back Chairs,” published in The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director, by Thomas Chippendale (London, 1754). Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Much like Gibbs’s doorcase designs, Chippendale’s designs for chairs are typically shown in groupings of three. One especially useful example is Plate 16, a group of three designs for ribband back chairs. Grouped together like Gibbs’s designs for doorcases, each of these are designs for complete chairs with pierced splats formed from thin, interwoven, and undulating ribbons and bows. All three chairs have elaborately carved cabriole legs and crest rails, and the design on the far right offers an option with a curved seat rail.

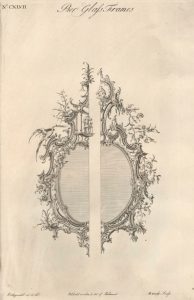

Pier glass frames, plate from The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director, by Thomas Chippendale (London, 1754)

Another similarly abstracted representational strategy employed by Chippendale is the bimodal composition utilized in the plates of designs for pier glass frames, frames for marble slabs, and shields for pediments. In these plates, alternative designs are presented as two halves of a larger whole, with each half bounded by a vertical discontinuation line and separated from the other by a negative space ample enough to allow carved ornament from both designs to spill into it, such as Plates 147 and 148. In the former, two alternatives for an elaborately carved oval mirror frame are given as separate halves. On the left, a stylized Chinese bird rests on the shoulder of the frame while, in the center, a figure stands inside an architectural pavilion. This is answered on the right by a seated buddha at the summit of the frame. Similarly, in the latter plate, four designs for slab frames or console tables are given as two left and two right halves, each variously containing similar Chinese figures, pavilions, and birds. These bimodal compositions allow Chippendale to present twice the amount of variety and choices and clearly suggest that such objects could be selected not only in a number of styles but with various options of associated ornament.

The hybrid and bimodal plates in the Director make clear Chippendale’s intention to present furniture and decoration which could be selected in a number of styles and alternatives. As published, Gibbs’s Book of Architecture did not contain any similar bimodal or hybrid compositions.

James Gibbs, two designs for chimney pieces, preparatory drawing for A Book of Architecture, Containing Designs of Buildings and Ornaments, by James Gibbs. Photo: Ashmolean Museum

However, among the preparatory drawings made for the publication of the Book of Architecture, now in the collections of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, are three intriguing bimodal drawings, two chimney pieces and one doorcase. Like Chippendale’s compositions, these drawings make the ornamental and stylistic language of internal architectural details a matter of consumer choice. Indeed, both the doorcase scheme and one of the two chimney piece designs are crowned, on one side, by a more restrained pediment and, on the other, a more exuberant broken pediment. In these plates, even more explicitly than in those ultimately published in the Book of Architecture, Gibbs reduces architectural style to its characteristic details and ornament and renders it as an option from which a discerning client might select. In this way, architectural style becomes a commodity which might be chosen from a catalog of options, much like the Chinese, Gothic, or ribband back chairs in Chippendale’s Director.