‘Lost in Austen’: Seeing Eighteenth-Century Print in TV and Film

Attributed to Brookshaw, Pair of George III Polychrome-painted and parcel-gilt satinwood secretaire bookcases, c. 1790. Almost certainly supplied to Colonel Sir Mark Wood, Piercefield Park, Monmouthshire, Wales. Christie’s, sold 13 Jun 2018.

Today’s post was written by Rachel Harmeyer, who is Ph.D. candidate in Art History at Rice University, where she studies the visual and material culture of the 18th and 19th centuries. –ANR

Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807), a Neoclassical history painter and founding member of the Royal Academy in London in 1768, created a sensation during her residence in London in the 1760s-1780s, with one printmaker remarking, “the whole world is Angelicamad!” Reproductive prints after Kauffman enabled her work to leap from the walls of the Royal Academy exhibitions and enter middle and upper-class homes. These prints were mined as an open design resource by decorative painters, cabinet makers (such as the satinwood bookcases seen here), textile and porcelain manufacturers, needleworkers, and needleworkers. Copyright law for artists was in its infancy, which permitted these makers to freely copy and adapt Kauffman’s art in multiple forms of other media. While this “objectification” of Kauffman’s work was not connected to her directly, these resulting artifacts have allowed me to gauge her broader reception and how her work was used in self-fashioning, the subject of my dissertation.

The Dashwood sisters in front of (non-Kauffman) neoclassical prints, in Sense and Sensibility, dir. Ang Lee, 1995. Courtesy of Columbia Pictures.

At some point during my research on Kauffman’s afterlife in visual and material culture, I began seeing her everywhere. This is a typical occupational hazard for an art historian, convinced as we are of the unique impact our research subjects. However, after a certain point, Kauffman’s sudden appearances crossed a critical threshold and began to intrude on my own domestic life. As an unabashed consumer of costume dramas in my downtime, I first noticed stipple engravings after Kauffman in the background of the 1995 BBC adaptation of Pride and Prejudice. This seemed reasonable as set dressing, but then I began noticing more and more. I noticed that the inclusion of art indexing Kauffman has almost become a trope itself in recent adaptations of Austen, even in irreverent ones. In what follows I attempt to gauge what cultural work Kauffman’s art is performing in these Austen adaptations.

In Sense and Sensibility (1995), actual paintings by Kauffman appear in the background of the stairwell in the scenes taking place at Norland because they were shot at Saltram House, the home of Kauffman’s important early patrons the Parkers. This group of history paintings, including Hector Taking Leave of Andromache, which Kauffman exhibited in the first Royal Academy exhibition in 1768, were destined for the Grand Saloon at Saltram. Now, they are placed in the liminal space of the stairway. Reflective of the couple who purchased them early in their married life, Kauffman’s Saltram paintings balance classical history with the common comforts of hearth and home, albeit on an elevated scale. To my way of overthinking, is this visual juxtaposition mirroring the tragic departure of Hector, who will leave Andromache in mourning, as the Dashwoods are at the beginning of Sense and Sensibility? In an example like this, it seems as though Kauffman’s presence is simply a built-in feature of filming in a British country house, something to be expected as part of using the historic structure as a backdrop—though their inclusion could be a conscious choice on the part of director, Ang Lee, screenwriter and star Emma Thompson, or the producers.

As I revisited other cinematic adaptations of Austen, I noticed that the prints after Kauffman seem inescapable in many of them. Angelica Kauffman’s stipple engravings seem to relentlessly appear in these adaptations. Does Kauffman’s work in reproduction in these films constitute mere set-dressing, is it subtext, does it mean anything other than a visual shorthand for femininity, love and courtship in an Austen period piece? Are they mistakenly (but secretly intentionally) trapped in the fictional world of these films, like the asynchronous protagonist in the ITV series, Lost In Austen (2008)?

Elizabeth Bennet with prints by Angelica Kauffman visible in the background, in Pride and Prejudice, dir. Simon Langton, 1995. Courtesy of BBC1 and A&E.

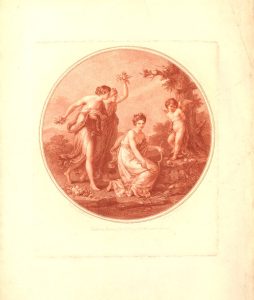

Stipple engravings after Kauffman lurk in the background of the Bennett’s home in Pride and Prejudice (1995). Most of the prints relate to Kauffman’s depictions of interplay between the Three Graces and Cupid described in Metastasio’s libretto Le grazie vindicate (1735). Euphrosine, Aglaia, and Thalia complain about various tricks Cupid has played on them and take their revenge by tying him to a tree and pelting him with flowers.

Ryland after Kauffman, Etiam Amor Criminibus Plectitur (Even Cupid is not Alien to Crime or Cupid Punished) 1777, British Museum

In this print, Cupid is tied to a tree and Thalia and Aglaia are dancing. Euphrosine, is bending Cupid’s bow as if to break it. Kauffman’s picture is one of female agency over matters of the heart—which works well in when applied to this scene, mirroring Elizabeth’s declaration, “to act in that manner, which will, in my own opinion, constitute my happiness, without reference to you, or to any person so wholly unconnected with me.”

In one way, the inclusion of these prints can be seen as a means to simply make the films looks more authentic, by attempting to recreate a seemingly historically accurate period interior. Over the mantel in the Bennett’s drawing room hangs a painting that seems to have been made after the Kauffman’s subject of The Graces Dancing. In this painting, the Graces and Cupid seem to have resolved their differences for the moment. The Graces dance as Cupid plays the harp. It appears in the background of many scenes (including those where the love is not so much in the air). However, it also appears in close up shots at significant moments: it is featured prominently right behind Mr. Bingley when he finally shows up in the last act to propose to Jane Bennett.

This pattern is followed in Emma (2020), shot at Firle Place in Sussex, where Cupid Disarmed by Euphrosyne makes a striking appearance and becomes important to the plot in two pivotal scenes. The print, this time a color stipple, appears prominently in Emma’s bedroom (for a lot of beautiful still shots and costume analysis, click here). Euphrosyne’s wresting of Cupid’s instruments away from him are paralleled in Emma’s ambitions as a matchmaker. (I am illustrating this print here with yet ANOTHER version, as it appeared translated onto a furnishing fabric made in Nantes, France.)

After-Kauffman-Cupid-Disarmed-by-Euphrosyne-Detail-of-Furnishing-fabric-Nantes-ca.-1815-Favre-Petitpierre-et-Cie-Victoria-and-Albert-Museum

In this poignant scene with Harriet, in which she sadly realizes that Emma wants her to refuse Mr. Martin, the print is visible on the far left, at the bedside. The print here holds its weight as a background character itself, mirrored by the servant on the right. Later in the film, Harriet visits Emma again and tells her that she will marry Mr. Martin after all. By this point, Emma has realized her mistake in manipulating Harriet and is actively seeking to redress the wrongs she has caused. The print is featured once again prominently on the right, perhaps to remind the viewer of Emma’s past mistakes.

Kauffman’s work in reproduction has been used to lend authenticity to the background of Austen adaptations, sometimes appearing meaningfully to mirror the plot of the film. What are we to make, however, of her works appearance in less-faithful, irreverent adaptations of Austen?

The Dowager Viscountess Dalrymple and honorable Miss Cartaret in front of prints by Angelica Kauffman. Still from Persuasion, dir. Carrie Cracknell, 2022. Courtesy of Netflix.

Persuasion (2022) provides us with an opportunity to consider what work these prints are performing in the background. For example, in a scene shot in the Blue Drawing Room at West Wycombe Park, the Elliots visit the Dowager Viscountess Dalrymple and honorable Miss Cartaret. The prints after Kauffman in the background appear to simply be part of the Neoclassical period decoration.

The Elliot family in front of anachronistic leopard print chairs and drinking out of solid gold teacups. Still from Persuasion, Netflix, 2022.

Contrasting with the deliberately anachronistic furniture featuring a loud leopard print in the shot of the Elliots sitting across from the Viscountess and her daughter, Kauffman’s work seems to be shorthand here for the type of artwork and artifacts one expects to see—part of the package deal. However, the particular prints after Kauffman used here, both aristocratic women who sat for painted portaits by her, circulated in prints as ideals of beauty, accomplishment, and motherhood. Part of the joke in Persuasion (2022) seems to be that the Dowager Viscountess and Miss Cartaret fall well short of being either interesting or aesthetically appealing. This mirroring is in keeping with the pattern established in earlier adaptations, making this version of Persuasion perhaps less irreverent than it thinks it is.

Overall, rather than reflecting the public, professional success of Kauffman as a Royal Academician and acclaimed artist, this re-use of her work as a backdrop for Austen’s narratives tends to focus narrowly on her work’s resonance with women in private, interior spaces. The juxtaposition of Kauffman’s subjects with those of Austen allows her stipple engravings and paintings to often become a visual shorthand for feminine subjectivity and desire in these films. Focusing on the female heroine’s perspective within the genre of history painting was indeed a strategy for Kauffman as a painter: it allowed her to achieve success in a masculine art within an institution that proscribed study of the male figure by women artists. However, the presence of Kauffman’s art in the background of these films reframes her work as intrinsically feminine and reflective of domestic interiors and marriage plots. Do these adaptations miss something crucial about Kauffman, or Austen? Undoubtedly. However, much like the protagonist in Lost in Austen, who spends the opening acts of the series insisting that the rewriting of her presence into the canonical text of Pride and Prejudice is a serious mistake, resisting Mr. Darcy and her own inevitable marriage plot, I have come to see the use of prints after Kauffman as a productive of new meanings, embracing this side quest as my own. As to the unlikely coupling of Austen and Kauffman? Let me not to the marriage of true minds admit impediments.