Karol Kłosowski and His Total Work of Art at the Silent Villa, Zakopane

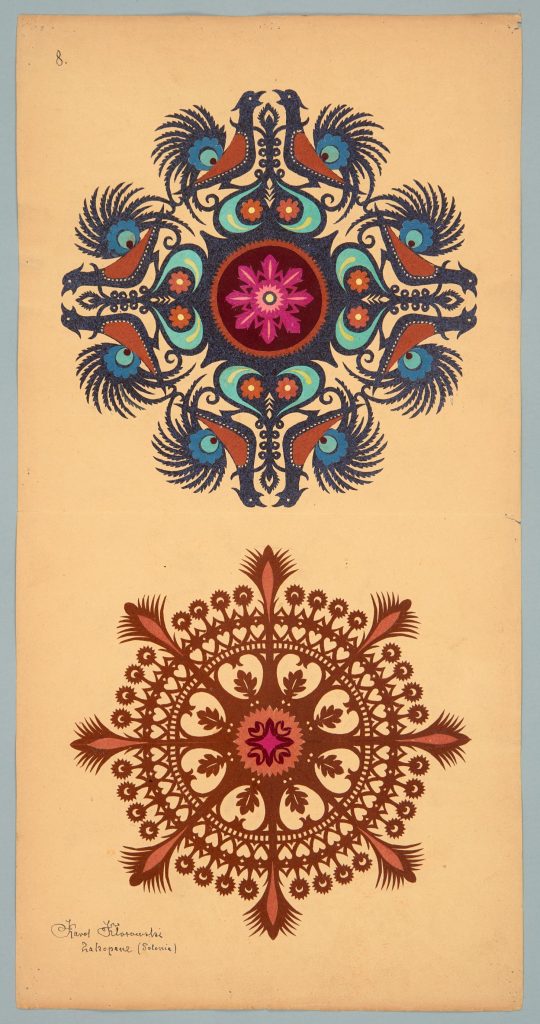

Mountain goat paper cutting by Kłosowski, c. 1908-25, colored paper on paper. Private collection, by descent from the artist. Photo courtesy of Natalia Klosowska.

This month we are delighted to feature a guest post from Julia Griffin, the co-editor of Young Poland: The Polish Arts and Crafts Movement, 1890-1918 (London: Lund Humphries, 2020) and co-curator, with Andrzej Szczerski and Roisin Inglesby, of the exhibition under the same title currently at the William Morris Gallery (until 30 January 2022). You can view the virtual tour of the exhibition with art critic Waldemar Januszczak here. She is a contributor to William Morris (ed. Anna Mason, 2021) and The Routledge Companion to William Morris (ed. Florence Boos, 2020). Her post explores the influence of the English Arts and Crafts movement on Young Poland, as artists like Karol Kłosowski concerned themselves with the creation of artistic environments within the domestic interior as an expression of national culture. This research is also the focus of her “Karol Kłosowski (1882–1971):The Last Young Poland Artist and a Genius for Ornament” in Young Poland. The Polish Arts and Crafts Movement, 1890-1918 (London: Lund Humphries, 2020).

In fond memory of Mr. Zygmunt Kłosowski (1951-January 3, 2022), painter, sculptor, and grandson of Karol Kłosowski.

Installation view of “Young Poland” at the William Morris Gallery, Walthamstow. Image courtesy of the William Morris Society of Canada.

The current exhibition at the William Morris Gallery, Young Poland. An Arts and Crafts Movement, 1890–1918 is dedicated to one of the most wide-ranging and original periods within Polish art. Characterized by the integration of fine and decorative arts, and a revival of handicrafts, Young Poland was part of the international Arts and Crafts movement originated by John Ruskin, the Pre-Raphaelites and William Morris. In 1795, following progressive invasion, Poland ceased to exist on the map of Europe, re-appearing only after World War One. For 123 years, Poland’s territory was divided between Russia, Austria and Prussia. Poles were subjected to persecution, including a ban on the Polish language, censorship, forced labor and political exile.

Kłosowski’s dining room with a display of his paper cuttings, Silent Villa. Private collection, by descent from the artist. Photo courtesy of the National Museum, Krakow.

Young Poland emerged as an expression of Polish people’s yearning for political independence and as a means of preserving their endangered cultural identity. Individual household objects such as a coffee cup, as well as entire decorative schemes of homes, churches and civic buildings became subversive carriers of Polishness. Artists and designers created a new visual language inspired by their lost country’s history, indigenous plants and local landscape, spirituality, as well as vernacular craft and architectural traditions. Like William Morris, Young Poland makers believed in everyone’s right to beauty in daily life and especially at home, the spiritual benefits of handiwork, and the equal value of all the arts and crafts irrespective of materials or techniques used.

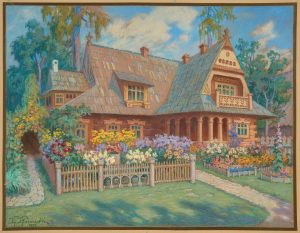

Karol Kłosowski (1882–1971) counts amongst Young Poland’s most original painters, designers, interior decorators and master-craftsmen with a Morrisean genius for ornament. He deserves a place amongst the ranks of foremost international Arts and Crafts makers. His masterful creation of the Silent Villa in the village of Zakopane at the foothills of the Tatra Mountains is a Gesamtkunstwerk of outstanding originality and quality. A half-orphan from a poor peasant family with no prospects for a higher education, Kłosowski was a child prodigy, whose artistic talent won him a series of scholarships to study at the best vocational craft schools and art academies in the Polish lands under partitions and abroad. During his passionate lifelong preoccupation with the arts, spanning over eighty years, Kłosowski produced a prolific output mostly intended for beautifying the home – whether at his own rural idyll, or the houses of others – namely pictures, furniture designs, architectural woodcarvings, kilims, lace mats, embroideries and paper cuttings.

Installation of Kłosowski’s paper cuttings in the “Young Poland” exhibition at the William Morris Gallery, Walthamstow. Image courtesy of Nicola Tree.

Despite its remarkable variety, Kłosowski’s art and design practice displays a great coherence of vision. It was guided by his belief in cultural democracy and by his quest to cultivate Poland’s endangered cultural heritage, best preserved in vernacular and folk-art traditions. This artistic philosophy is not only self-evident in the work but is also expressed in Kłosowski’s numerous articles and his textbook Paper Cuttings: Designs Based on Folk and Naturalist Motifs (1923). He stated: ‘pragmatism only serves the sustenance of a vegetative form of human existence. It is beauty which gives life fullness, dignity and worth.’ Kłosowski’s resulting oeuvre is characterized by a central integration of fine and decorative arts, combined with an underlying joy of making, frequently in the face of adversity. Each item is of exquisite design and execution, and notable emotive impact. It was the apparently humble paper cutting that should perhaps be viewed as the single most significant art form within Kłosowski’s diverse output due to the ideological implications of this medium. The paper cutting is one of the most traditional manifestations of Polish folk art.

Karol Kłosowski’s chisels for paper cutting. Private Collection. By descent from the artist. Photo courtesy of Natalia Klosowska.

This practice flourished in the 19th century, being commonly used by peasants from diverse regions of the Polish lands under partitions to decorate the interior of their cottages – initially in the windows as a substitute for net curtains and subsequently as colorful ornaments used for decorating the walls, usually beneath pictures, particularly popular at Christmas time. They were traditionally made with shears by folding colored papers along multiple axes of symmetry (from one up to about 16). Kłosowski first tried his hand at paper cuttings at the age of eight, making do with newspapers. Nevertheless, by the time he had turned 11 his designs became sought-after decoration at local peasants’ weddings. He continued to perfect the craft to seek solace following a teenage disappointment in love.

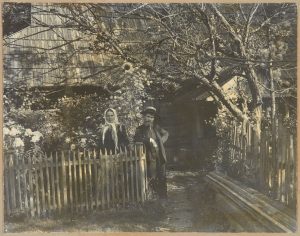

Photography of Karol Kłosowski and his wife Katarzyna outside Silent Villa, c. 1907-15 (Private Collection, by descent from the artist).

Kłosowski had initially left the art of the paper cutting behind when he moved away from his village in Podolia (today’s Ukraine) to pursue a comprehensive, decade-long artistic education. It is notable that with all the benefit of exposure to the world of high art at the Fine Art Academies in Vienna and Kraków, Kłosowski chose to revive this modest art form 12 years later, not long after settling down into married life in Zakopane. Having wedded the Highlander poetess Katarzyna Gąsienica Sobczak (1866–1915) in 1907, Kłosowski moved into her modest Podhale hut-cum-guesthouse known as Sobczakówna, and embarked on a series of enlargements and extensions transforming it into the House Beautiful he renamed Silent Villa.

His initial motive behind resuming paper cutting was to decorate the Silent Villa for Katarzyna’s gratification, however the medium soon turned into Kłosowski’s manifesto of cultural democracy. He never lost the joy of making, which helped sustain him through the loss of his first wife in 1915 and during a period of the Second World War when both of his children were conscripted into forced labor camps.

Wood Grouse paper cutting by Kłosowski, c. 1908-25, colored paper on paper. Private collection, by descent from the artist. Photo courtesy of the National Museum, Krakow.

Kłosowski’s paper cuttings show most clearly his Morrisean genius for repeating patterns and outstanding sense of colour, presenting a joyful, fantastical and virtually multi-sensory world of Tatra mountain plants, animals, insects and birds. His chirping crickets, hissing snakes, hairy caterpillars, sprightly squirrels, dignified wood grouse and mountain goats are reminiscent of the rhythmic beauty, enchanting charm and humor of Morris’s iconic printed cotton designs such as ‘Brother Rabbit’ (1882) or ‘Strawberry Thief’ (1883). What is notable is his strikingly contemporary use of color, with an ability to harmonize bold and subdued tones in a single composition, and his capacity to abstract without losing the character of the depicted creatures. Some of Kłosowski’s designs were more overtly patriotic, including multiple renditions of the crowned eagle, Poland’s national emblem. The paper cuttings’ geometric composition and formal perfection are reminiscent of the mandala, hinting at Kłosowski’s inherent understanding of the natural world. They invite reflection and meditation, whilst embodying Morris’s concept of ‘art as a joy to the maker and user’.

A selection of Karol Kłosowski’s paper cuttings, c. 1908-1925, colored papers on paper. Private collection, by descent from the artist. Photo courtesy of the National Museum, Krakow.

In the early 20th century the paper cutting was becoming a disappearing craft, much to Kłosowski’s distress, as peasants began to replace it with cheap German oleographs in the hope of achieving greater gentility. It was then that the medium became Kłosowski’s staple mode of artistic expression. It is clear that he viewed it as both a manifesto of cultural democracy and a key repository of authentic national heritage, stating:

The paper cutting has grown out of the basic human desire for beauty, out of the same motive as behind any other art work created by people from more cultured social strata. In quiet, impoverished villages – in the drabness of life – the populace resort to materials and making in search for joy and happiness . . . I strongly hope that in the present time of trying to recover our own style on the basis of our own old models: castles, moss-clad manor houses and roadside shrines, we will create our own architecture; similarly, the paper cutting is a treasure trove of characteristically Polish motifs, which will serve as the basis for creating rich local ornamentation already under way.

A corner of Kłosowski’s studio with a display of artwork and paper cuttings, Silent Villa. Private collection, by descent from the artist. Photo courtesy of the National Museum, Krakow.

Despite a first-rate education and access to the Kraków art world, Kłosowski chose to settle down in the village of Zakopane, where he led the sort of quiet rural existence that Morris longed for but could never experience at Kelmscott due to pressing duties in London. In Zakopane Kłosowski took up many of the media and art forms he grew up with and embraced the local vernacular traditions, celebrating and elevating the status of folk art. He must not, however, be mistaken for a folk artist. The art forms he deliberately engaged with were his form of cultural politics aimed at distilling Polishness and practicing cultural democracy. Kłosowski’s meticulous and ingenious paper masterpieces continue to decorate Silent Villa interiors today.

Many thanks to Ms Ula Bukowska, Mr Jacek Bukowski, the late Mr Zygmunt Kłosowski, and Ms Natalia Kłosowska with appreciation for their efforts to preserve their (great)grandfather’s legacy and for making photographs and research materials available. Special thanks to William Morris Gallery, National Museum in Kraków, Polish Cultural Institute, Lund Humphries, the Tatra Museum, Roisin Inglesby, Rowan Bain, James Gray, Andrzej Szczerski, Kamila Hyska, Anna Wende-Surmiak, Anna Kozak, Zbigniew Moździerz, Helena Pitoń, Anna Myczkowska-Szczerska and Ted Griffin.