Performing Shakespeare with Rubens: Mid-Nineteenth Century Royal Command Performance at Windsor Castle

This week we feature a blog post from Éilís Smyth, who recently completed her PhD at Kings College London on Shakespeare and royal command performance. Her post examines a staging of “Macbeth” in the Rubens Room at Windsor Castle, a moment when royal residence, theatrical performance, and the display of art coexist in fascinating ways. She is currently working on revising her thesis for publication.

We went over to the Rubens Room, after 8, & Shakespeare’s splendid Tragedy of “Macbeth” was extremely well given. The scenery, including the Cave or Cawdor scene with the apparitions, was admirably managed, & the dresses beautiful, & most correct… It is a most interesting, thrilling, & heartrending play.[1]

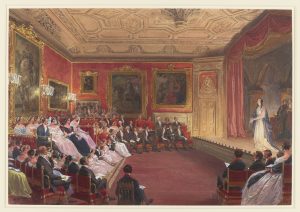

Louis Haghe, “The performance of ‘Macbeth’ in the Rubens Room,” 1853, watercolour and bodycolour with gum arabic over pencil, Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 919794.

So wrote Queen Victoria on the evening of 4 February 1853. That night’s performance of Macbeth was one of a series of dramatic productions at court known as the Windsor Theatricals – forty-five royal command performances of English plays that took place at Windsor Castle between 1848 and 1861. The programme of the Windsor Theatricals was dominated by Shakespeare. About a third of the plays performed were Shakespeare’s, and seven out of the ten seasons of Windsor Theatricals opened with a Shakespeare production. This series of mid-nineteenth century performances represented the most sustained and regular royal patronage of the dramatist at any court since the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, and – given available evidence – at any court since Shakespeare’s plays were first performed for Elizabeth I and James VI and I. My research considers the negotiation between the royal family and Shakespeare through the specific mode of royal command performance, and I’m interested in the politics of the privacy of court performance during the period.

The first years of the Windsor Theatricals took place on a bespoke stage in the King’s Drawing Room which was known in the nineteenth century as the ‘Rubens Room’ because of its decor. Following the 1853 production of Macbeth, Victoria commissioned a favourite artist, Louis Haghe, to memorialise the performance in watercolour.

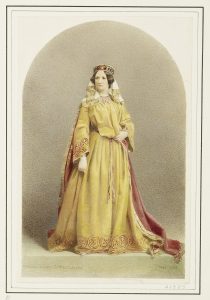

In Haghe’s painting, renowned Shakespearean actress Ellen Kean performs Lady Macbeth’s famous monologue – ‘Out, damn’d spot! Out I say!’ – just paces away from Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, the Duchess of Kent, Princess Ada of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, and six of the royal children. The other distinguished guests sit outside the makeshift box created for the royal family on the dais. You can just make out a crowd of royal servants peeking in the doorway of the western wall.

Edward Henry Corbould, “Mrs Charles Kean as Lady Macbeth,” May 1853, watercolor and bodycolor, Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 921325.

This watercolor is one of just a handful of images of Windsor Theatricals performances – the productions were highly private affairs and there was no media presence at the court theatre. Interestingly, the queen did not place this depiction of a court performance of Shakespeare with the many other commemorative watercolors of public Shakespeare performances she commissioned. These make up a separate Theatrical Album – a gift from Albert in which she kept a pictorial record of the plays they most enjoyed together. She placed the painting instead in one of her Views Albums – nine highly sentimental and personal volumes of watercolors commissioned by Victoria and Albert as records of memorable events and places in their familial lives. So preserved amidst images of their children’s birthday celebrations, family homes (including a watercolor of the queen’s private bedroom), and significant trips, was a painting of the monarch watching Shakespeare in the drawing room at Windsor Castle, her children at her feet. Its place in one of the Views Albums physically located and marked the performance of Shakespeare at Windsor as domestic and familial celebration – situating this material commemoration of royal command performance at court firmly in the private, domestic sphere of royal family life.

Louis Haghe, “The Discovery of Duncan’s murder, ‘Macbeth’ Act 2 sc. 1,” 1853, watercolor with gum arabic, Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 921323.

Haghe’s watercolor is not just a record of this ephemeral court performance of Shakespeare, however, it also documents the interior of the Rubens Room at a particular moment in time. Victoria and Albert were keen to preserve the interiors of their homes in watercolor – leaving a permanent record of what is often transient in royal properties. Just a few decades before, for example, the ceiling of the Rubens Room had featured Antonio Verrio’s grand illustration of Charles II driving through the sky in a triumphal car, loudly celebrating the restoration of the monarchy. The ceiling had been dismantled early in the nineteenth century by George IV. In keeping with the royal interest in documenting the appearance of its various residences, Haghe’s payment of £35 for the watercolor was made for his depiction of ‘the interior of the Rubens room in Windsor Castle during the performance of Macbeth.’[2]

After the play’s transfer to the Princess’s Theatre on Oxford Street, which Victoria attended on 18 February 1853, the queen commissioned three watercolours of her favourite tableaux from the public production. See, for example, Haghe’s depiction of the discovery of Duncan’s murder, from Victoria’s Theatrical Album. In correspondence with the queen’s dresser about this watercolor, Haghe wrote that he understood ‘perfectly’ that the paintings of the Princess’s production should be ‘only what takes place on the stage, without showing any part of the theatre.’[3]

Part of what Victoria wanted to preserve in the earlier painting of the court performance, then, was the Rubens Room as a theatre, and the performance of Shakespeare against the backdrop of her drawing room. Haghe made rough renderings of the Rubens which can be seen on the western wall (it seems apropos to mention here that a few years later a journalist wrote that if Haghe had ‘lived in the days of Rubens, he might have been one of the greatest of his scholars’, though one must wonder if such high praise might be attributed to the artist’s consistent receipt of royal patronage).[4] Paintings visible in the painting of Macbeth include Rubens’ Self Portrait (left) The Holy Family with St Francis (right), and the equestrian portrait of King Philip II of Spain (middle) attributed to the studio of Rubens.

detail of Louis Haghe, “The performance of ‘Macbeth’ in the Rubens Room,” 1853, watercolour and bodycolour with gum arabic over pencil, Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 919794.

So while Haghe’s painting offers us a glimpse of what these private performances, and this purpose-built, small-scale court theatre looked like, it also showcases the royal family’s role as patron and collector of fine art. Here, the Crown curated within one image a display of its art – held in trust for the nation – and its patronage of the national poet. Neither, however, were for public consumption. If you want to further explore the connection between Shakespeare and the royal family please visit the fantastic online exhibition curated by the team from the AHRC funded project ‘Shakespeare in the Royal Collection’. Check out, too, how Martin Blazeby used Haghe’s painting to digitally reconstruct the Rubens Room theatre in the video here.

[1] RA VIC/MAIN/QVJ (W) 4 February 1853 (Princess Beatrice’s copies). Retrieved 20 September 2021.

[2] Payment to Louis Haghe for paintings of Macbeth, 20-22 February 1853, Royal Archives, PPTO/PP/QV/PP2/1/3118

[3] Louis Haghe, Letter to Marianne Skerrett, 20-22 February 1853, Royal Archives, PPTO/PP/QV/PP2/1/3118.

[4] Quoted in Carly Collier, Victoria & Albert: Our Lives in Watercolour (London: Royal Collection Trust, 2019), p. 22.