“Orchestrating Elegance:” Alma-Tadema and the Marquand Music Room

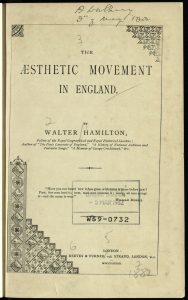

Until recently, scholarship had treated the domestic interiors of the Aesthetic movement as retreats from real life. From 1868 onwards, the poet Algernon Swinburne and the Oxford don Walter Pater, among others, championed “art for art’s sake,” and they declared art’s autonomy from an ameliorative social function, whether intellectual or moral. Thus detached from the public sphere, “the essence of the movement,” according to Aesthetic apologist Walter Hamilton in 1882, was “the union of persons of cultivated tastes to define and to decide upon what is to be admired.” The domestic sphere became the foremost expression of this admiration and the environment for the display of these objects. As Hamilton explains, “followers must aspire to that standard in their worlds and lives.” This formulation usually forecloses any possibility of direct political engagement for such interiors. As Elizabeth Prettejohn observes, Aestheticism often seems to “denote a frivolous . . . elevation of art above the serious concerns of political and social life.” The British artist, designer, and socialist Walter Crane, however, declared exactly the opposite in a 1905 lecture. “House decoration,” he concluded, “is almost synonymous with civilization.”

Attributed to George Collins Cox (American, 1851–1902) Marquand Music Room: view of the room and ceiling from the alcove, c. 1888–90. Nassau County Department of Parks, Recreation, and Museums, Photo Archives Center.

Henry Gordon Marquand would have agreed, but perhaps not the way the socialist Crane would have hoped, as revealed by the exhibition catalogue Orchestrating Elegance: Alma Tadema and the Marquand Music Room. The book weaves a complex cultural web around a singular object, the grand piano designed by Lawrence Alma-Tadema in the 1880s for the music room of Henry Gurdon Marquand’s New York mansion at 68th Street and Madison Avenue, the only known furniture designed on commission by the artist. Alma-Tadema designed the pianoforte, as well as a suite of furniture, window and door curtains, and wall coverings, as well as drawing together a team of artists to contribute to the room’s decorations. The book accompanied the exhibition of the same name held at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts (June 4–September 4, 2017). The book is a multi-strand text, following the stories of Alma-Tadema as artist, Marquand as patron, Johnstone, Norman, & Co. as makers of the piano, and well as the fate of the furniture on the art market. Exhibition curators Kathleen Morris and Alexis Goodin provide the majority of the text, with contributions from art historian Melody Barnett Deusner and conservator Hugh Glover. The essays are interspersed with two “galleries” of images: one set shows the music room in historical photographs while the second features the twelve piece of the Marquand Furniture Suite brought together for the exhibition.

As noted in a previous post, Alma-Tadema orchestrated his own domestic and working life in two studio-houses he created in St. John’s Wood, with his wife Laura (also an artist) and his daughters Laurence and Anna, an artist as well. Alma-Tadema’s first piano design was for his own home, a gift of a decorated instrument to his wife in 1873, followed by a larger and grander one suitable for entertainment and designed by the architect George E. Fox with Byzantine decoration in 1878. This richly decorated instrument was placed in Alma-Tadema’s studio, and the lid’s interior was lined in parchment to be signed by those who used it in their art. This engagement with musical instruments even inspired John Broadmoore and Sons Ltd. to sell a design they called “Alma-Tadema Upright Grand.”

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, designer; Johnstone, Norman & Co., London, manufacturers; Model D Pianoforte and Stools, 1884–87. Clark Art Institute.

Against this backdrop, Melanie Barnett Deusner’s essay places the piano within the richly layered context of the music room of Marquand’s New York mansion, one room in a series of social spaces within the home that communicated Marquand’s social and cultural status as well as the global networks he created through his investments and railway lines. She discusses Marquand’s Madison Avenue mansion as a “material map” of his achievements and investments. Marquand’s financial fortunes fell in 1901, while Alma-Tadema’s did not fare much better upon his death in 1912. As Morris discusses in her history of the furniture makers Johnstone, Norman, & Co. in the volume, the expansion prompted by the popularity of the Alma-Tadema piano ultimately led the firm to financial difficulties in the 1890s. They eventually folded in 1911. In a later essay, Morris also describes the details of the music room commission and the team of artists and craftsmen involved in its creation under the direction of Alma-Tadema. Many of Marquand’s rooms were decorated according to themes, such as his Byzantine bedroom, while Alma-Tadema alighted upon a Greco-Pompeian décor for the music room.

Marquand had purchased Alma-Tadema’s Amo Te, Ama Me (1881; Fries Museum, Leeuwarden) and commissioned A Reading from Homer in 1882 (1885; Philadelphia Museum of Art). Frederic Leighton would contribute a ceiling panel, while Edward Onslow Ford made the fire place surrounds and ornaments. The room also featured Marquand’s collection of Greco-Roman antiquities, set off by a furniture suite designed by Alma-Tadema against a backdrop of matching textiles and walls featuring a Greek motif stenciled on silk.

Alma-Tadema, “A Reading from Homer,” 1885. Philadelphia Museum of Art, The George W. Elkins Collection, 1924.

The artist drew upon ancient precedents, but in a way that adapted their antique style to the function of the room. Morris notes that the room followed a strict internal logic that distinguished it from the taste for historicist interiors. Steinway & Sons manufactured the piano and sent it to London for decoration. Alma-Tadema oversaw the ornamentation of the case, including the painted fallboard by Edward Poynter showing dancers and musicians in a grove. The exhibition, unlike the book, could evoke these interdisciplinary exchanges in three-dimensions. In addition, there are YouTube videos of piano concerts that hint at the power of these environments in formulating a version of gesamtkunstwerk before Richard Wagner, “an ideal work of art in which drama, music, and other performing arts are integrated and each is subservient to the whole.”

The book is a group portrait of a room that also serves as the biography of a piano. One cannot escape the luxurious materiality of these objects, from the detailed photographs in glossy color to the delineation of primary and secondary woods in the report by furniture conservator Hugh Glove. By detailing the questions that remain as well as the various avenues of research, listing sale prices and advertisements, a fuller picture of the business of commissioning interiors emerges, a methodology that approximates Marquand’s own perspective as a patron and investor.