William Morris and Lawrence Alma-Tadema

A version of this post also appeared on News from Anywhere, the blog of the William Morris Society

Ellen Epps (later Gosse), Portrait of Laura, Lady Alma-Tadema, probably entering the Dutch Room at Townshend House, Regent’s Park, 1873. Private Collection.

William Morris (1834-1896) and Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912) were contemporaries, but very little seems to connect them in terms of artistic ideals and interests other than an overlapping circle of friends, including Edward Burne-Jones. Alma-Tadema was also a founding member of Morris’s Society for the Preservation of Ancient Buildings, founded in 1877. Yet the historical record is, as usual, more complicated. Morris wrote to his daughter Jenny on October 17, 1888 about the elaborate decorations undertaken by Alma-Tadema at Townshend House, near Regent’s Park, where the artist lived from 1871-5: “I don’t admire them: they appear to me too much made up of goose giblets and umbrellas.” The artist’s daughter Anna Alma-Tadema created a series of watercolors of the house, including a view of the study, that suggests the wide range of artistic interests and inspiration, including what Charlotte Gere has identified as a dado of resist-dyed cotton from the Dutch East Indies. Perhaps these were the goose giblets? Nonetheless, critics considered the kind of artistic living fashioned by Alma-Tadema at Townshend House to be commensurate with the approach to interior decoration advocated by William Morris. The journalist Daniel Moncure Conway considered the house, “the most complete rendering of the effects at which William Morris and Burne Jones have aimed in their efforts at beautifying London households.”

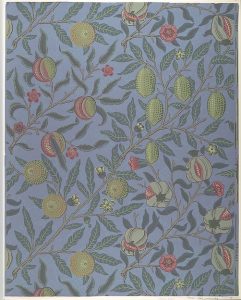

The visual records suggest that Alma-Tadema was interested in the work of William Morris. The recent Alma-Tadema exhibition Alma Tadema: At Home in Antiquiety featured the stunning Epps Family Screen, usually in display in the British design galleries at the V&A. Alma-Tadema created it in cooperation with his student Laura Theresa Epps, who would later become his wife. The six-fold screen shows Laura’s family at dinner, gathering below an inscription from Aesop’s fables celebrating family unity. They gather in a dining room hung with Morris’s Pomegranate wallpaper, designed c. 1865. The design may have been a favorite of Laura’s, as it appears in a watercolor by the artist Ellen Epps (Laura Epps’s sister, who later married Edmund Gosse) from 1873, Laura Alma-Tadema Entering the Dutch Room at Townshend House (at the top of this post; now in the collection of Peter and Dorothy Wright). The décor paid homage to the artist’s Dutch identity, albeit with an eclecticism characteristic of the Aesthetic movement: Laura strides through a doorway mostly hidden by an Old Dutch cabinet filled with linen, but the dado below Pomegranate appears to be comprised of Japanese tatami mats.

These intersections bring to mind the range of domestic spaces in which one can explore the art and life of William Morris. The William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow was the Morris family home from 1848 to 1856, and today it is a gallery that considers the artists life and work as well as the art produced by Morris’s circle of friends and colleagues. Incidentally, the William Morris Gallery is a member of the Artists’s Studio Museum Network, a “network of small museums based in artists’ former homes or studio.” In fact, there are three affiliates of the studio museum network related to William Morris. Red House in Bexleyheath was commissioned by Morris from the architect Philip Webb in 1859. The family lived there until 1865, and it is currently a National Trust property that is open to the public. The furnishing do not remain in situ but conservation work has revealed previously lost elements of the interior, including a Pre-Raphaelite wall painting. It was at Red House that Morris founded “the Firm” of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co.

Morris’s political convictions came to the fore during his time at Kelmscott House in Hammersmith, overlooking the Thames, Morris’s residence from 1878 until his death in 1896. It is still a private house and is not open to visitors. Those in search of a Kelmscott experience will have to explore Kelmscott Manor in the Cotwolds, opened to the public during certain times thanks to the Society of Antiquaries in London. These residences and the range of Morris’s artistic production make it difficult to name a single “artist’s studio home” for Morris. Yet the diversity of the Morris “studio-home” environments provides it own sort of richness, from the idea of the artist decorating the interior at Red House to the meetings of the Hammersmith Socialist Society at Kelmscott House.

The Hammersmith Branch of the Socialist League, William Morris is fifth from the right in the second row. Image courtesy of https://www.marxists.org/archive/morris/photo/hsmithsl.htm

Barbara Penner and Charles Rice commented upon what they termed the “many lives” of Red House in an essay from 2013, and their concluding thoughts provide a suggestive model for scholars considering artists’s houses: “tracing how [Red House’s] interior has been constructed and propagated through the circulation of images and objects, we touch on what makes the interior modern: the modern interior has a life–and a significance–all its own.”