“Looking Out, Looking In” at Association for Art History 2018

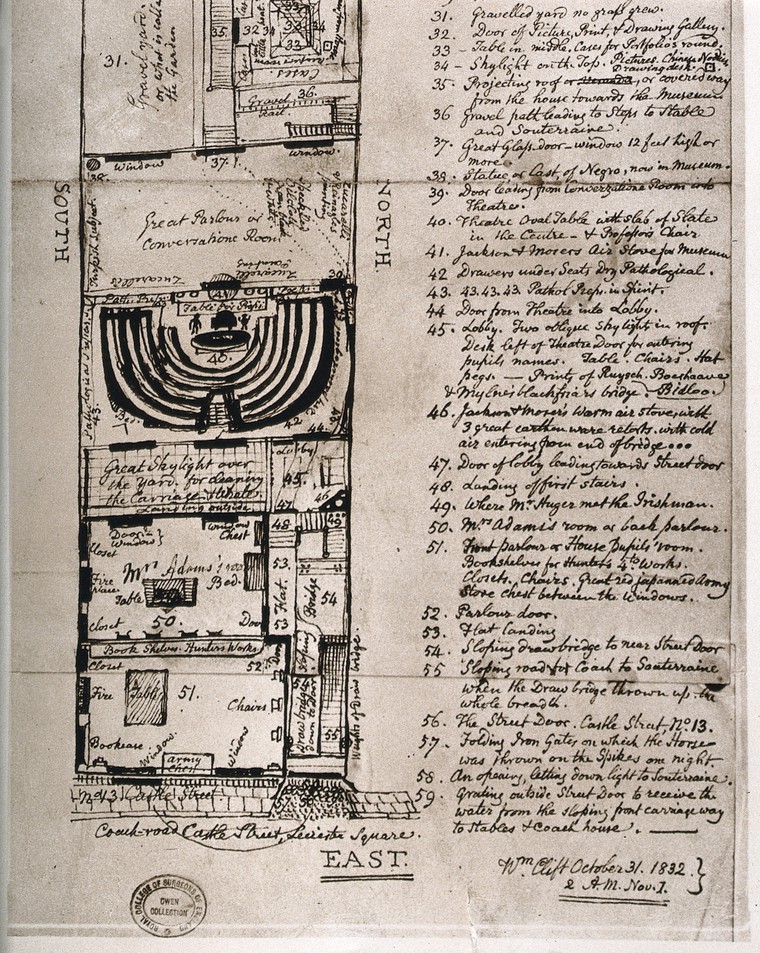

John Hunter’s residence: Ground plan of Hunter’s premises at No. 28 Leicester Square in 1792, as drawn in 1832. Photograph. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

I represented Home Subjects at the 2018 meeting of the newly-renamed Association for Art History which took place in London April 5-7. I was one of three coordinators on a panel titled “Looking Out, Looking In,” which sought to bring together academic art historians with contemporary art practitioners to explore a range of issues related to the study of and reinterpretation of historic interiors. One of the persistent themes here at Home Subjects is that it is extraordinarily tempting to look at images of interiors in the past as precise renderings of how interiors looked in a particular period. In the case of all private and public collections, and in interiors generally, images have too often been used in precisely this way; to know how the interior was decorated and how pictures were hung. Yet, it is crucial that we not interpret such images and texts as transparent and factual documents of an interior that no longer exists. Using the tools available to the art historian, we should approach these images as representations of space that should be treated with extreme care. The authors of images and catalogues were not engaged in uninterested documentary projects; they were historical actors whose productions adhered to established conventions for representing interiors and collections.

The purpose of the “Looking Out, Looking In” panel was to explore these questions, and also to ask how interiors can be represented by historians, artists, and curators in a way that does justice to both the evidence we do have while accounting for all of the things we do not know. We had a wide range of contributions to address this topic from a variety of methodological viewpoints.

William Bond (engr.) after J.C. Smith, The New Gallery at Cleveland House in John Britton, Catalogue Raisonné of the Pictures belonging to the most honourable The Marquis of Stafford, in the Gallery of Cleveland House (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1808), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

I introduced the themes of the day by presenting a case study of Cleveland House, which reflected on the methodological problems presented by my own current research project. The image of the gallery’s interior illustrated at left, which was made by J.S. Smith in 1808 to accompany a guidebook to the collection, creates the impression of a room that is sparsely furnished in order to accommodate the connoisseurship that the male figure in the image undertakes. However, this images leaves out far more than it reveals, obscuring many elements of the gallery’s elaborate decorative interior not to mention the active and lavish aristocratic social life for which it provided a stage.

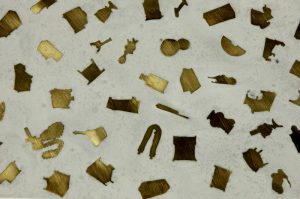

Following the introduction, we started the day with presentations from several practicing artists, who are using innovative approaches to re-present and re-imagine interiors for contemporary audiences. Jennifer Gray talked about how her art practice has helped her illuminate meanings in historical interiors and objects, which offered her a new way to think about collections of objects and how the viewer might encounter or interact with them. One project involved re-imagining spaces from Sir John Soane’s Museum in London into contemporary pieces of jewelry and technology. Gray has also been working on a project to use an important historical source for interiors, seventeenth-century probate inventories, to represent the types of common and rare objects with which an individual’s life would have been populated. This approach was the basis for the “Portrait of Marie Palluau.” The photograph here represents a small piece of Gray’s work, which uses an inventory of Palluau’s possessions to make the interiors in which she lived visible in a way that makes sense to contemporary audiences. Similarly Catrin Huber used an imaginary dialogue with an ancient Roman wall paintress who decorated the rooms at the Casa del Criptoportico in Pompeii to illuminate how such imaginary conversations help Huber explore the process through which she allows historical site to illuminate contemporary practice and vice versa.

While the morning’s speakers were focused mainly on using art and digital technology to inform both contemporary practice and the understanding of historical interiors, the afternoon’s papers delved into the historians’ toolkit in order to illuminate how we can use such tools to interrogate and re-interpret historic spaces. Camilla Pietrabissa examined the scientific cabinet of Joseph Bonner de la Mosson at the hôtel de Lude in Paris. While historians of science have tended to focus on scientific specimens and instruments, as well as the processes of collecting them, Pietrabissa’s paper showed how reconstructing the logic of the interior in which these objects were arranged and displayed, in addition to the gardens that interpenetrated the building’s interior, can also illuminate the epistemological categories that underpinned the study of natural history in the eighteenth century. Helen McCormack continued with the theme of science in the interior with a look at the home of physician and anatomist Dr William Hunter, which was located at 16 Great Windmill Street in London. McCormack used interior views and floor plans to describe how the practices of science and the development of interiors in which they took place were mutually-informing and reinforcing. Sarah Shivers explored the complex history of a rare medieval church that has survived to the present day, asking how the various histories of its interior may be reconciled with contemporary needs. Finally, Shatvisha Mustafi discussed a program of commissioning paintings for the interiors and exteriors of public buildings in mid-twentieth century India.

Whether for use in a television documentary, historic site, museum, or academic journal, visual representations of historic interiors can provide valuable evidence of how interiors looked. Yet, as I hope this brief introduction to the myriad issues raised in approaching one historical interior suggests, while there are many benefits to such an approach, there are also things we can miss in this process. Images of interiors were never merely documentary, but themselves carry meaning which can illuminate how interiors looked and functioned. The techniques and aesthetic choices made by people who represented interiors must always be considered if we are to understand how interiors were understood in the past, and this session provided a rich set of discussions from which to consider these questions.