Priming the Eye, Producing Splendor

Editor’s note: Today we present the second in our series of posts previewing the upcoming Home Subjects panel “Art and/in the Private House” at the annual meeting of the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies in Minneapolis, Minnesota, March 30-April 2 2017. Next up is Laurel O. Peterson, who is completing her dissertation titled “The Decorated Interior: Artistic Production in the British Country House, 1688–1745” at Yale University. –ANR

Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini, Triumph of Caesar, c. 1713. Kimbolton Castle (now Kimbolton School), Kimbolton, Huntingdon. Photo credit: Laurel O. Peterson

In 1713, the Venetian artist Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini completed his ambitious mural, a Triumph of Caesar, painted for Charles Montagu, fourth earl (later first duke) of Manchester. This painting, which wraps around the Grand Staircase at Manchester’s seat of Kimbolton Castle, represents a procession of more than thirty figures. Flags and ribbons flap in the breeze, and gold and bronze urns and trophies glint in the light. Tambourines rattle, trumpets sound, and babies bawl. For Manchester, a former ambassador to Venice and Versailles, as well as an important patron of the arts, such a painting conjured the pomp of the continental courts with which he was familiar and expressed his own cultural taste.

At the turn of the eighteenth century mural painting was the dominant fashion for elite interior decoration in Britain. Artists, primarily of continental extraction, transformed interior spaces with these decorative paintings, covering ceilings and walls with mythological and allegorical scenes. The style had its origins in courtly contexts; upon his restoration to the throne in 1660, Charles II had employed numerous painters, sculptors, and craftsmen to bring Windsor Castle and Whitehall Palace up to date with the latest fashions from France and Italy. In the chapel at Windsor—then one of the grandest royal spaces—the muralist Antonio Verrio covered ceilings and walls with The Last Supper and The Resurrection, complemented by marble foliate carvings by Grinling Gibbons in the lower register. Following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, mural painting gained increasing popularity among members of a broader elite—particularly among Whig aristocrats like Manchester. In country houses and town houses alike, the murals could reinforce the power of their patrons, serving as both political and cultural statements. At the same time, as fixed decoration, mural paintings were uniquely suited to shape and inform a viewer’s experience of the interior of the house.

Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini, Triumph of Caesar, c. 1713. Kimbolton Castle (now Kimbolton School), Kimbolton, Huntingdon. Photo credit: Laurel O. Peterson

Given Manchester’s attention to incorporating fashionable luxury objects within his own domestic settings, the choice of mural for the principal staircase in his country estate would have been carefully orchestrated. He had brought Pellegrini back to England with him from Venice, in part to serve as a decorative painter for his newly restored and renovated Kimbolton Castle. The subject chosen by Manchester and Pellegrini—the Triumph of Caesar—had an illustrious pedigree, deriving from Andrea Mantegna’s famed interpretation of the subject (ca. 1485-1506, Royal Collection). Mantegna’s Triumph—composed of nine canvases—was been purchased by Charles I and has hung in Hampton Court Palace since the 1630s.

Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini, Triumph of Caesar, c. 1713. Kimbolton Castle (now Kimbolton School), Kimbolton, Huntingdon. Photo credit: Laurel O. Peterson

Like Mantegna before him, Pellegrini carefully represented material objects throughout the procession. Gold and bronze punctuate the throng of bodies, the line of trophies helping to guide the viewer’s gaze through the space. Toward the front, an urn and jug gleam. Pellegrini has carefully rendered the undulating surface of the urn, and has highlighted the elaborate golden handle of the ewer. The gold in Pellegrini’s painted metalwork may have matched with other objects at Kimbolton, such as gilded mirrors and seat furniture. Among the objects Manchester imported from France were fifty bronze busts; some of them likely ended up at Kimbolton. The repeating forms of trumpets and trophies thus served dual roles: emphasizing the movement of the procession, and reinforcing the presence of gilt objects throughout the house.

Pellegrini’s mural, with its attention to material objects, reinforces the emphasis on material grandeur at Kimbolton. Like many of his fellow English ambassadors, Manchester developed a taste for courtly splendor while on the continent. In both Italy and France, he acquired textiles, furniture, and works of art, seeking to decorate his residences in keeping with the latest fashions. His five ambassadorial gondolas were grand enough to subsequently be purchased by the King of Denmark. He returned from France with, among other goods, nineteen looking glasses, furniture upholstered with fashionable St. Maur silk, a harpsichord, and a portrait of Louis XIV. In Venice, he not only procured velvet wall hangings for Kimbolton, but he also purchased 3300 yards of velvet and damask on behalf of Sarah, the duchess of Marlborough, who was the in the midst of planning the decoration of Blenheim Palace. The Duchess praised Manchester’s shopping skills, telling him “you are so good I can go to none else.”

Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini, Triumph of Caesar, c. 1713. Kimbolton Castle (now Kimbolton School), Kimbolton, Huntingdon. Photo credit: Laurel O. Peterson

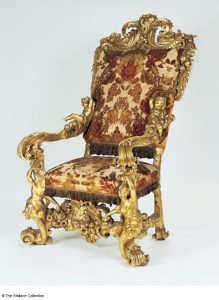

One of the most striking re-workings of Mantegna’s composition is Pellegrini’s representation of Caesar’s throne. With its curling acanthus forms dramatically carved on the chair leg, this seat is in keeping with contemporary Italian furniture production. Manchester himself owned such furniture, having purchased walnut and parcel gilt chairs, which may have been similar to an example now in the Wallace Collection. Upon his return to England in 1708, such elaborate furniture would have been largely unknown in Britain, and might have appeared almost exotic. The material world on display in Manchester’s home, then, is insistently Venetian—a reference to his ambassadorial past.

The mural thus reiterates and re-contextualizes the material experience of other principal rooms of the house. The mural, while representing a world distant from that of eighteenth-century Huntingdonshire, would have been in conversation with the other spaces in the house. For the visitor, immersion within the scheme serves not only to awe and impress, but also primes him or her to be attentive to the visual experience of the interior as a whole, to the dynamic interplay of paintings, textiles, metalwork, and furniture.