A Bonfire of Regency Vanities: The Wanstead House Sale of 1822

Richard Westall, 1765–1836, British, Wanstead House, undated, Watercolor and graphite on medium, slightly textured, cream laid paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Editor’s note: Today we are featuring the first in a series of posts previewing an upcoming Home Subjects panel at the conference Creating Markets, Collecting Art, which will convene at Christie’s Education in London July 14-15, 2016. Our first poster/speaker is Diana Davis, who recently completed her doctoral thesis, titled British Dealers and the Making of the Anglo-Gallic Interior, 1785-1853, at the University of Buckingham. –ANR

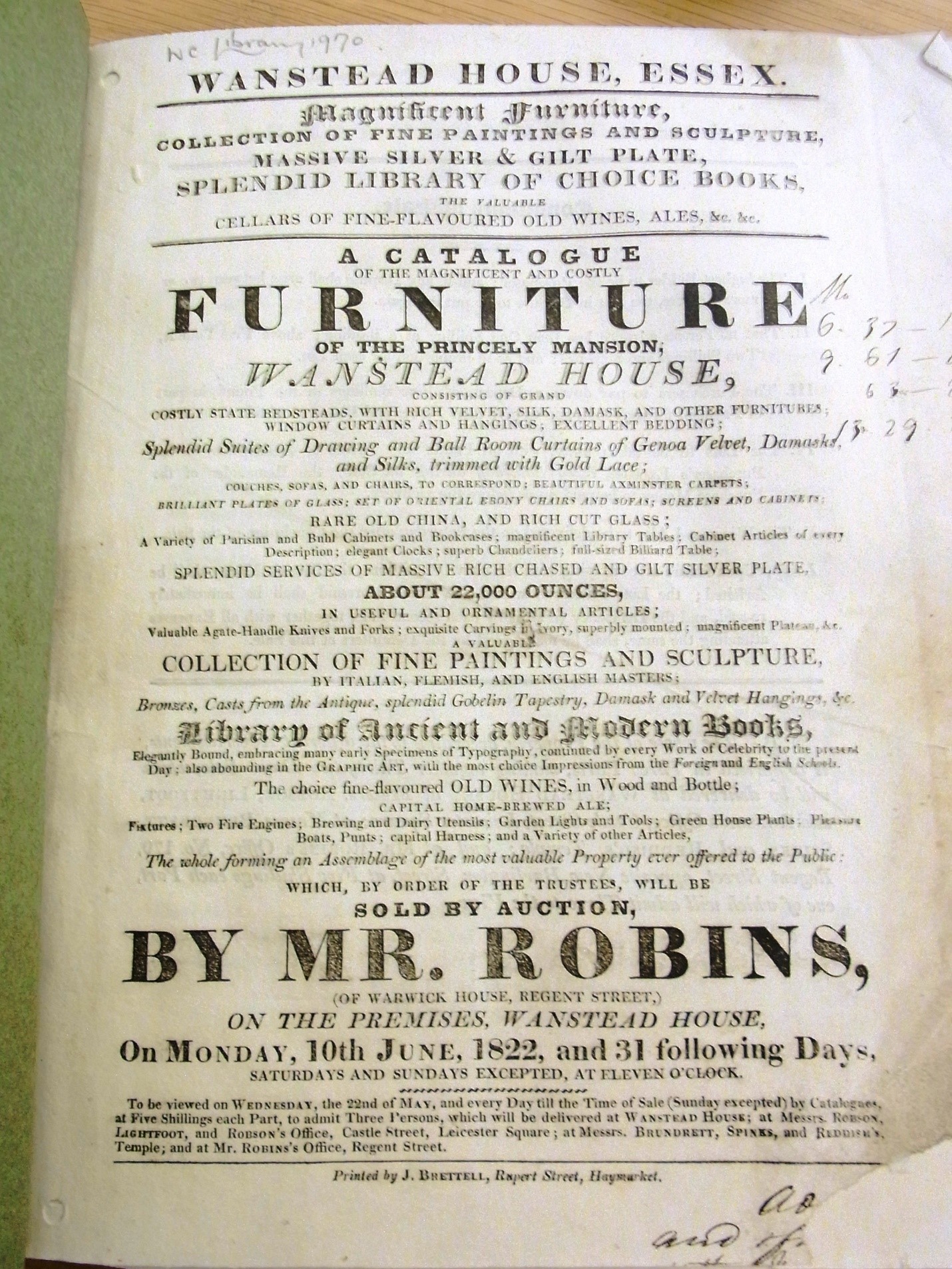

On June 10, 1822, the luxurious contents of Wanstead House, a vast Palladian mansion in Essex, were put under the hammer in an auction lasting 32 days. The Wanstead House sale symbolized a moment when conspicuous consumption wreaked devastating loss. Built a century before, Wanstead featured a suite of eleven opulent parade rooms decorated and furnished by William Kent. In 1805 it was inherited by Catherine Tylney-Long, heiress to the Child banking fortune. After her marriage in 1812 to the Duke of Wellington’s nephew, William Wellesley-Pole, the couple embarked on a sumptuous refurbishment of the house. However, by 1820 Catherine’s enormous fortune had been squandered. The couple could neither pay their mounting debts nor afford the upkeep of the estate, fleeing to France to escape their creditors. The proceeds of the sale failed to save the house and by 1825 ‘one of the noblest houses in England’, as A New History of Essex (1769) described it, had been demolished. The sale was therefore seen as both tragic and scandalous, a poignant exposure of a private house and belongings to public scrutiny. A bonfire of Regency vanities, Wanstead exemplified the ‘princely mansion’ but provided an object lesson in where the extravagant consumption required to create this ideal could lead.

The furnishings acquired by the Wellesley-Poles demonstrated the radical changes in collecting practice which had occurred over the previous quarter century. Ancien régime furniture, which before 1800 would have been regarded in Britain as old fashioned and ‘second hand’, came to be seen as a worthy addition to the grandest of houses. By the 1820s opportunistic dealers in London and Paris, profiting from the revolutionary dispersal sales in France of the contents of royal and aristocratic collections, had transformed the taste of the British elite. The Wellesley-Poles overlaid Wanstead’s existing palimpsest of Kentian and ebony furniture, blue and white porcelain and pictures with acquisitions of sumptuous continental furniture and decorative arts epitomizing a century of French aristocratic taste. Most notable was the astonishingly rich collection of boulle furniture, much attributable to the workshops of André-Charles Boulle.

Two narratives of the Wanstead auction emerged in parallel. One, in the popular press, castigated the Wellesley-Poles’ lifestyle as socially irresponsible. It memorialized Wanstead as one of England’s grandest houses, destroyed in a decade by one man’s profligacy. The other, represented by the catalogue, used the house and its contents as a template for the fashionable interior by showcasing the furnishings in the setting for which they had been purchased. The catalogue, compiled by the auctioneer George Robins, was written as a targeted marketing tool, offering prospective clients a luxurious lifestyle which included everything from furniture, pictures and books to fine wines, garden plants and pleasure boats. Robins understood the value of the objects he was selling. Significantly, he described the furniture attributed today to André-Charles Boulle as ‘antique’, an early use of the term as it is understood today, but listed boulle revival furniture simply as ‘Parisian’. However, the catalogue’s title page listed the boulle furniture after state bedsteads, plate glass, Axminster carpets, and ‘excellent bedding,’ suggesting that Robins was deliberately promoting a magnificent lifestyle rather than the celebrated collection as Wanstead’s key selling point. In marked contrast, Phillips’ catalogue for the sale of William Beckford’s Fonthill Abbey in 1823, another landmark auction of the early 1820s, promoted the house not as a ‘home’ but as the provenanced collection of a connoisseur.

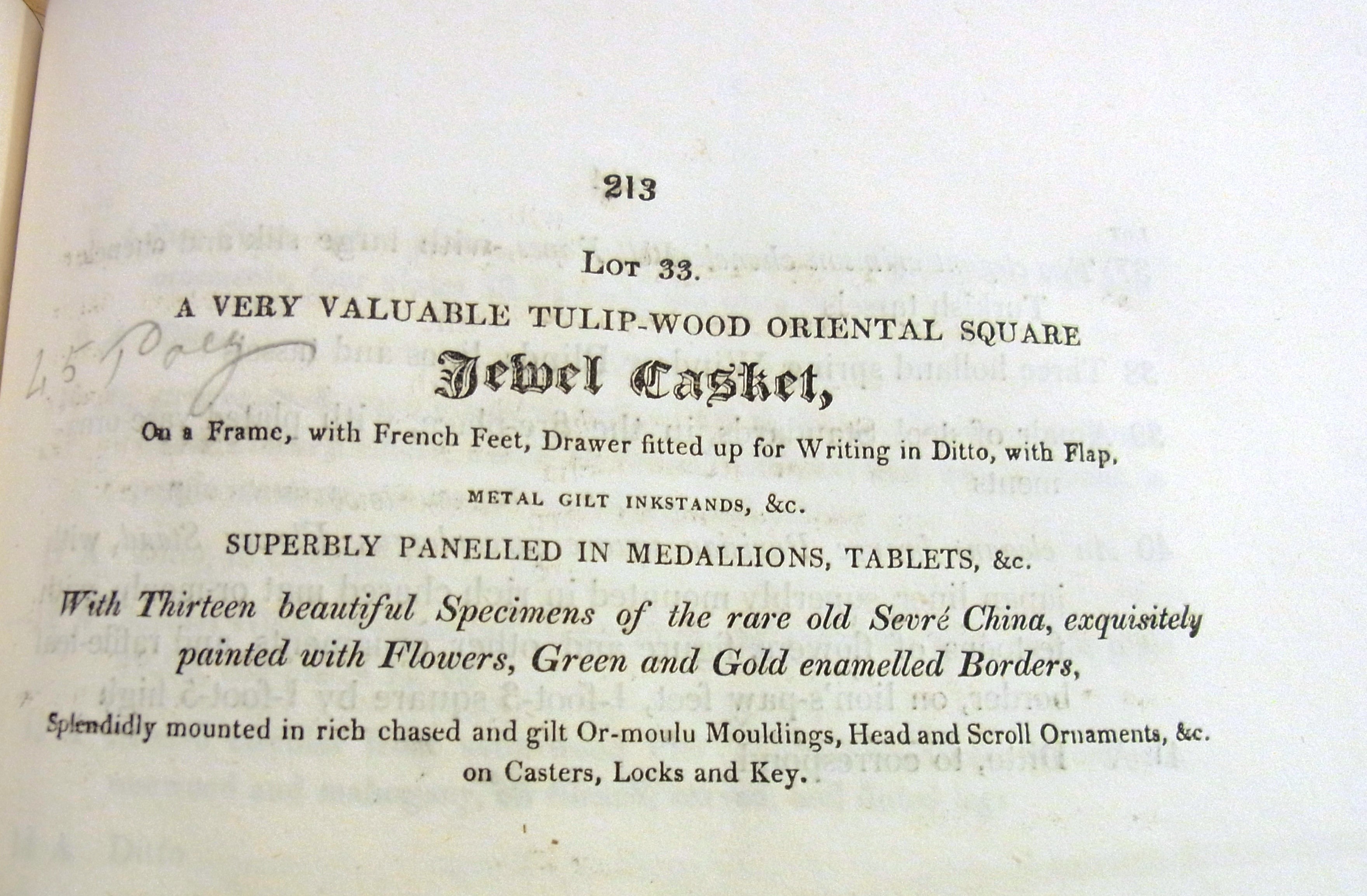

The catalogue was not illustrated, nor did it contain any room descriptions. Instead, Robins evoked Wanstead’s decorative interior by selling the contents of the house as it had been lived in, complete with sumptuous carpets and curtains. Buyers could view and buy the complete ‘look’ from the curtain ties to the cabinetwork. The porcelain, plate, pictures and books were sold on dedicated days. Robins’ expansive prose created pictures in words, emphasizing colour, quality, size, texture, and opulence. An ‘oriental Japan’ worktable was ‘elegant’, ‘top lined crimson Genoa velvet’, its octagon work bag ‘filled with puckered silk’. Moreover, he directed purchasing choice, highlighting 89 lots which he considered noteworthy, such as the ornamental plate, with an innovative indented display and different typography as the illustration shows.

The porcelain-mounted coffre à bijou described in this listing, today attributed to Martin Carlin, is probably one of the ones now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Wanstead catalogue therefore provides a window on Regency fashion, confirming the role of the auctioneer not simply as a purveyor of luxury goods but as an arbiter of taste.